While James Kim joined the fight to defeat the Empire of Japan with the U.S. Army, his brothers in Shanghai began a quiet struggle to resist it from within. They made themselves an American underground in the Japanese-occupied metropolis, trying to find ways to resist the Imperial Japanese Army and the Kempeitai — the military police that was the Gestapo of Japan.

Japan’s reign of terror in the Shanghai International Settlement began in the first weeks of the occupation. The Kempeitai rounded up British and Americans who had been officials of the Shanghai Municipal Council, Shanghai Municipal Police officers, business leaders, and journalists, imprisoning them in a residential apartment building turned interrogation center that became infamous as the Bridge House.

The new Japanese overlords of the Shanghai International Settlement seized western-owned businesses and buildings, expelling many British, Americans, and other foreigners from their homes and leaving thousands with no means of support. Suddenly impoverished, Shanghai’s western foreigners went hungry as wartime food shortages made even finding enough to eat a struggle.

Peter Kim soon became a leader of the American community’s efforts to assist its newly destitute people. He volunteered to work for the American Association of Shanghai, which tasked him with organizing food supplies for the needy and establishing a relief center in the grounds of the Shanghai American School. In the summer of 1942, the association also placed him on its War Prisoners Committee, which aided U.S. Marines who were prisoners of war in Shanghai after being captured at the U.S. Legation in Beijing and on Wake Island in December 1941.

An even greater task fell on Peter Kim in the summer of 1942. Diplomatic negotiations between the United States and Japan, conducted through neutral Switzerland, had reached a deal for the exchange of civilians held by the two combatant nations. The American Association entrusted Peter with working with the Swiss Consulate in Shanghai to select and organize Americans for repatriation from Shanghai. After his efforts, the Italian ocean liner SS Conte Verde left Shanghai in July 1942 with 639 U.S. citizens on board, heading for a rendezvous in southern Africa with the ship that the U.S. Department of State had chartered for the exchange, the Swedish liner MS Gripsholm.

The Americans who departed Shanghai for repatriation included Judge Milton Helmick of the U.S. Court for China in Shanghai, who before the war had been synonymous with U.S. law enforcement in the city as judge of the U.S. extraterritorial court, and U.S. Marine Corps Major Gregon Williams, Assistant Naval Attache in Shanghai, who later commanded the 6th Marine Regiment in the Battle of Okinawa and during the Korean War served as chief of staff of the 1st Marine Division during the Inchon landing and the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir.

A U.S. government lifeline for Americans in Shanghai began in 1942, and it eventually benefited the Kim family through their sole U.S. citizen in Shanghai: Betty. In April 1942, the U.S. Department of State and the Swiss Foreign Ministry began a program to aid American civilians in Japanese-occupied China by providing them with relief loans administered by the Swiss Consulate in Shanghai. Betty, the only family member eligible for the program, began receiving these loans in October 1942.

The financial support enabled the family to buy food in Shanghai’s markets and remain in their modest house. Moreover, it allowed them to maintain their independence as Americans, instead of finding themselves compelled by poverty to collaborate with the Japanese.

Everything changed later in 1942, after U.S. victory in the Battle of Midway in June turned the tide in the Pacific and the Allied counteroffensive at Guadalcanal began in August. Japan now saw the thousands of white foreigners living in Shanghai as a threat, a possible resistance movement in a key center of its empire, so it decided to herd them into prison camps. The internments began on November 5, 1942, and from January to April 1943 group after group assembled for their journeys into a dozen internment camps, called “Civil Assembly Centres” by the Japanese.

Japan’s internment of thousands of British, American, and other Allied nation civilians has survived in current memory almost solely from the 1987 motion picture Empire of the Sun, directed by Steven Spielberg and starring a young Christian Bale (shown above), which was based on the novel of the same name by J.G. Ballard, an internment camp survivor who became a well-known author.

The Kim family found themselves left out as their fellow Americans disappeared behind barbed wire. Japan’s race policies left Asians out of the internment of white foreigners, expecting that they would accept becoming subjects of the Japanese Empire, the new order in Asia. Even Betty, a U.S. citizen, was allowed to live normally and move around the city, subject only to a requirement that she wear an armband identifying her as American, which she soon ignored.

The Kim family proved the Japanese to be wrong. They remained steadfastly loyal to their fellow Americans in Shanghai and to the distant United States, even though it had kept them out for more than 15 years. Soon after the internments began they started to find ways to assist interned Americans and resist the Japanese occupation, becoming the underground that the Japanese had tried to prevent.

Peter became the lifeline to the outside world for Americans in the internment camps. In March 1943 he went to work for the Swiss Consulate in Shanghai, whose diplomats represented the United States in looking after the safety of U.S. citizens in the city. The Swiss Consul, Emile Fontanel, hired Peter to serve as the consulate’s representative in matters relating to interned Americans. Peter organized the delivery of relief supplies from the Swiss Red Cross and reported problems in the camps to Fontanel, who passed the reports to the U.S. Department of State.

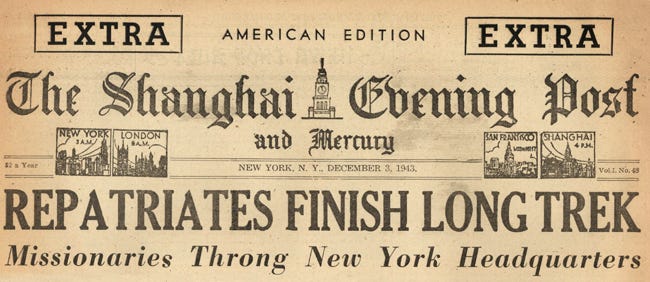

When the United States and Japan conducted another exchange of civilians in the autumn of 1943, again using the Gripsholm as a chartered mercy ship, Peter once more organized the release of internees from the camps. Under Peter’s direction, almost 1,000 people left Shanghai’s internment camps and boarded the Japanese repatriation ship Teia Maru on September 19, bound for a rendezvous with the Gripsholm in the neutral territory of Portuguese India and safe passage home.

While Peter Kim worked overtly to aid his fellow Americans, his actions contributing to headline news back in the United States, his girlfriend in Shanghai since before the war was covertly connecting the family to U.S. intelligence. Ruth Moy was a Chinese-American living in Shanghai since the 1920s whose estranged husband Ernest Moy had escaped the Japanese invasion and become a Nationalist Chinese official with the organization responsible for supporting the U.S. 14th Air Force. She had also been left out of the internments even though she was a U.S. citizen married to a Nationalist Chinese official. U.S. Army intelligence established contact with her and began preparing to make her the linchpin of future intelligence collection operations in Japanese-occupied Shanghai.

The younger brothers had to wait for their opportunity to do something to resist the Japanese. Richard, 15 years old when the internments began, and a friend named Olof Lindstedt, whose family from neutral Sweden had not been interned, would ride their bicycles to outside of a newly constructed camp in the western outskirts of Shanghai which held mainly Americans, called Chapei. They hoped that they could see their friends behind the barbed wire, particularly their classmate Ted Hale, whose family had given their two Irish Terriers to the Kims and the Lindstedts to keep during their internment. Richard and Olof could only dream of finding their friends and somehow smuggling things to them through the barbed wire.

Forces far beyond their awareness would soon draw the entire Kim family in Shanghai into the war raging across China.

Describing the Shanghai internment camps in this post was possible solely thanks to the research and writing of Greg Leck. His book Captives of Empire: The Japanese Internment of Allied Civilians in China, 1941-1945, published in 2006, is a unique resource on the history of the internment camps with detailed information on the camps and the people who lived through them that cannot be found anywhere else. Captives of Empire can be purchased here.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.