In the summer of 1944, after two and a half years under Japanese occupation, the Kim family in Shanghai finally became connected to the distant U.S. armed forces. Contact with the outside world came in the form of the same man who had found Peter and Richard in Kukong, on the road between Shanghai and free China—Lieutenant Jack Young.

Lieutenant Young had clandestinely arrived in Shanghai in early July 1944, after his chance encounter with Peter and Richard in Kukong. Young carried the pao chia identification card given to him by Peter, and his destination was the house of Peter’s girlfriend, Ruth Moy, who was the estranged wife of Ernest Moy, Young’s friend and relative by marriage. This web of relationships had led to Ruth becoming an asset of U.S. Army intelligence. Young was relying on her to provide a safe house while he stayed in Shanghai to collect information on Japanese troop movements and economic conditions in Japanese-occupied China.

The remaining Kim family members in Shanghai became further intelligence assets for Jack Young. Only two of the five Kim brothers remained in Shanghai, David and Arthur. David, familiar with Peter’s relationship with Ruth as a 27-year-old adult, received orders from Young through Ruth. Arthur then had to carry them out. Only 14 years old, Arthur was young and harmless-appearing enough to move around the city without arousing the suspicion of Japanese soldiers or police patrolling the streets.

Arthur had to carry out Jack Young’s orders without knowing who was behind them or what their purpose was. David kept Arthur in the dark about Jack Young, since he had no need to know. The less that Arthur knew, the less that he might divulge if Japanese soldiers or police captured and questioned him. It was a hard introduction to intelligence tradecraft for a fourteen-year-old boy in a world war.

U.S. military intelligence collection in Shanghai in 1944 became a task for a 14-year-old boy, on a bicycle too big for him. To move around the city carrying out Lieutenant Young’s orders, Arthur had to use the family’s only means of transport, an adult-sized bicycle that Peter had purchased many years earlier. The bike was too large for Arthur, who could barely reach the pedals and the ground from its seat, but there was no other choice since a child-sized bike would have been an out of reach extravagance for the family since the 1930s.

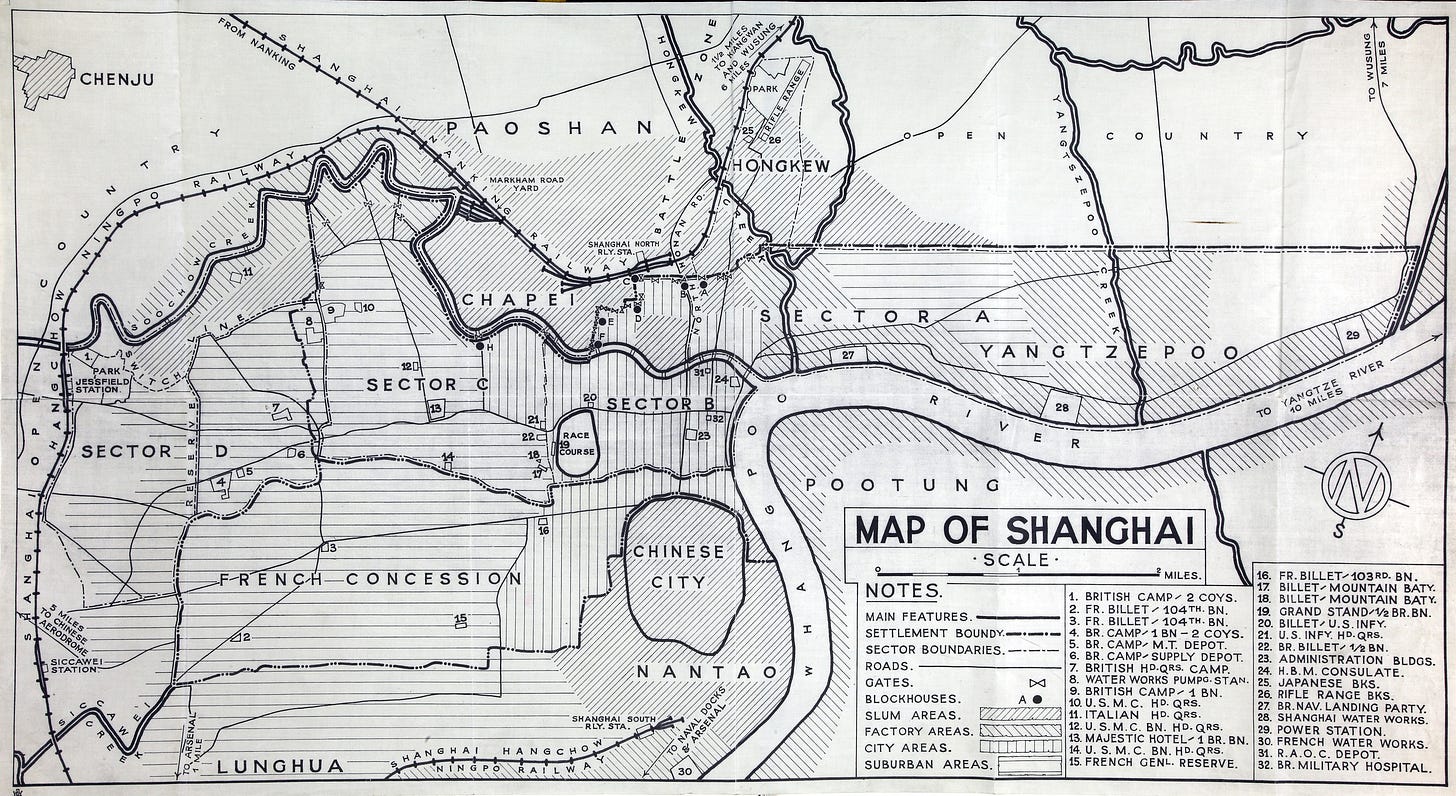

Young’s orders repeatedly sent Arthur to Hongkew, the Japanese quarter of Shanghai, to purchase Japanese newspapers. These newspapers published reports on Japanese troop movements, economic conditions in Shanghai, and other information of military significance, making them valuable open-source intelligence.

Arthur would set off from the family house on Route Père Robert in the French Concession and pedal several miles to Hongkew. Along the way he had to cross Suzhou Creek on an arched stone bridge, at whose center peak stood a pillbox manned by a Japanese soldier. In Hongkew he would buy a copy of every Japanese newspaper that he could find and then haul the stack of papers back home to the French Concession.

During one return trip he was struggling to walk his bicycle across the bridge, which was too steeply sloped to pedal, when the Japanese soldier in the middle of the bridge stopped him. This soldier expected anyone crossing the bridge to bow while passing him. Arthur tried to bow, but the adult-size bicycle that he was trying to hold upright had handlebars as high as his chest, making it impossible for him to bow more than part way. Enraged by the seeming lack of respect, the Japanese soldier slapped Arthur hard across the face, almost knocking him over. The bayonetted rifle in the soldier’s hands could have come next. Arthur dropped the bicycle to bow fully, and the Japanese soldier, finally satisfied, dismissed him.

These missions continued until Jack Young left Shanghai in November 1944. Young returned to Kunming, where he reunited with Ernest Moy and was able to congratulate Arthur’s brother Richard on his December 7 enlistment in the U.S. Army. Arthur, David, Betty, and their mother remained in Shanghai, where their lives became increasingly precarious as Japan continued to lose the war.

They did not know that their brother James, whom they had not seen for seven years, was at that very moment preparing for his first fight in the long U.S. island-hopping campaign from the South Pacific to Japan’s home islands. Soon he would see combat in the battles to liberate the Philippines.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.