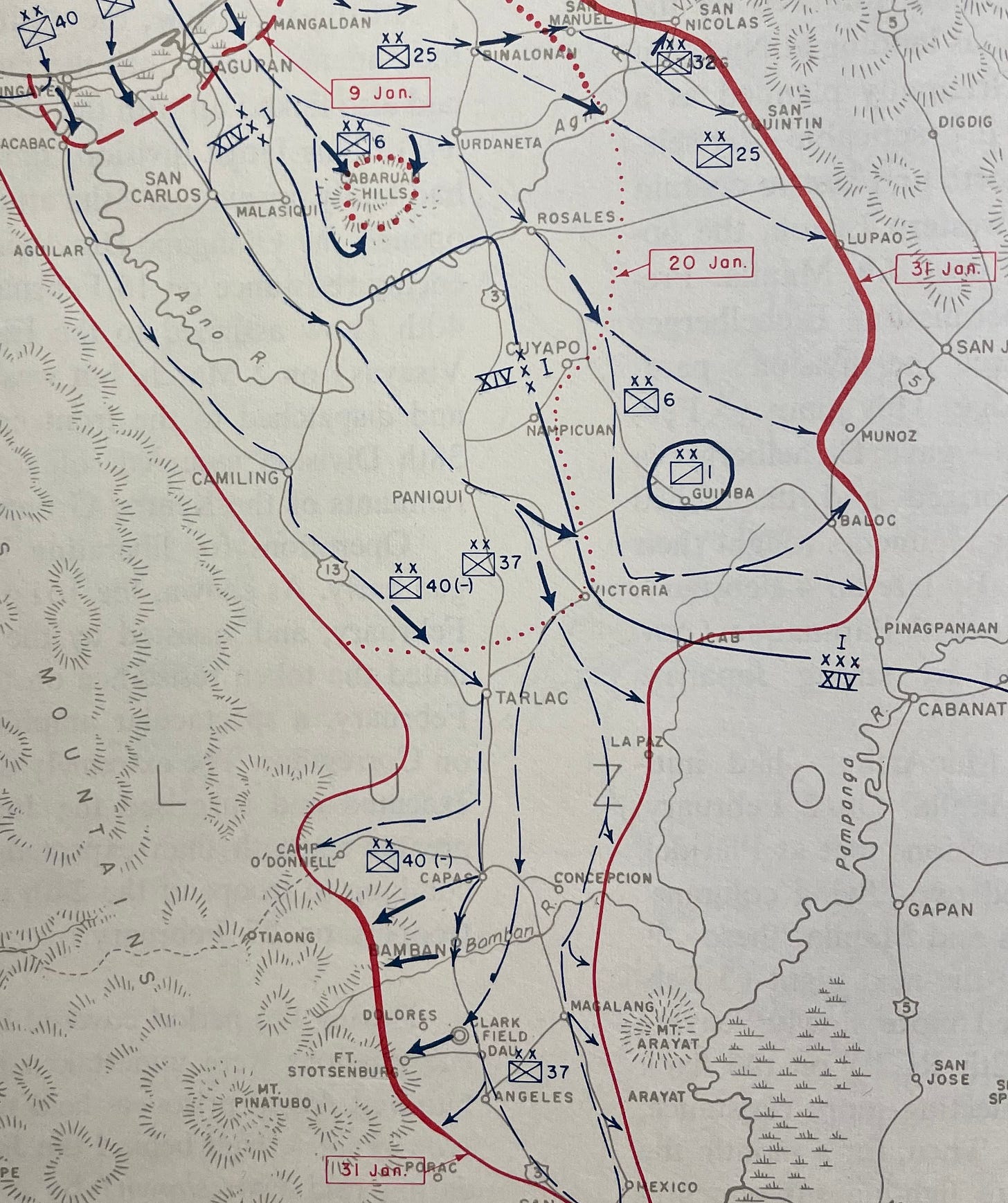

The 40th Infantry Division advanced on the far right of the U.S. forces driving south from Lingayen toward Manila. By January 22, the division’s reconnaissance troop had reached Camp O’Donnell, a prewar Philippine Army base that had become the final destination of the Bataan Death March in April 1942. The next day, the 160th Infantry Regiment entered the town of Bamban, and the 108th Infantry Regiment followed it to the Bamban River. Beyond the river were Clark Field, the main U.S. airbase in the Philippines before the war, and Fort Stotsenburg, another prewar Philippine Army base.

Philippine guerillas and civilians reported that Japanese forces were gathering in the hills overlooking Clark Field and Fort Stotsenburg, called the Bamban Hills. The 40th Infantry Division soon found that the Japanese has several thousand infantry with tanks and artillery dug in at Clark Field and the Bamban Hills, positioned to block the highway to Manila.

In the hills were two ridges honeycombed with networks of tunnels, linking caves made into emplacements for several 6-inch naval guns—long-barreled artillery made to be fixed to warships and coastal defenses. These long-ranged weapons could hit the routes that U.S. forces needed to move troops and supplies past the hills to Manila. The naval guns had to be knocked out to clear the way for the advance to continue.

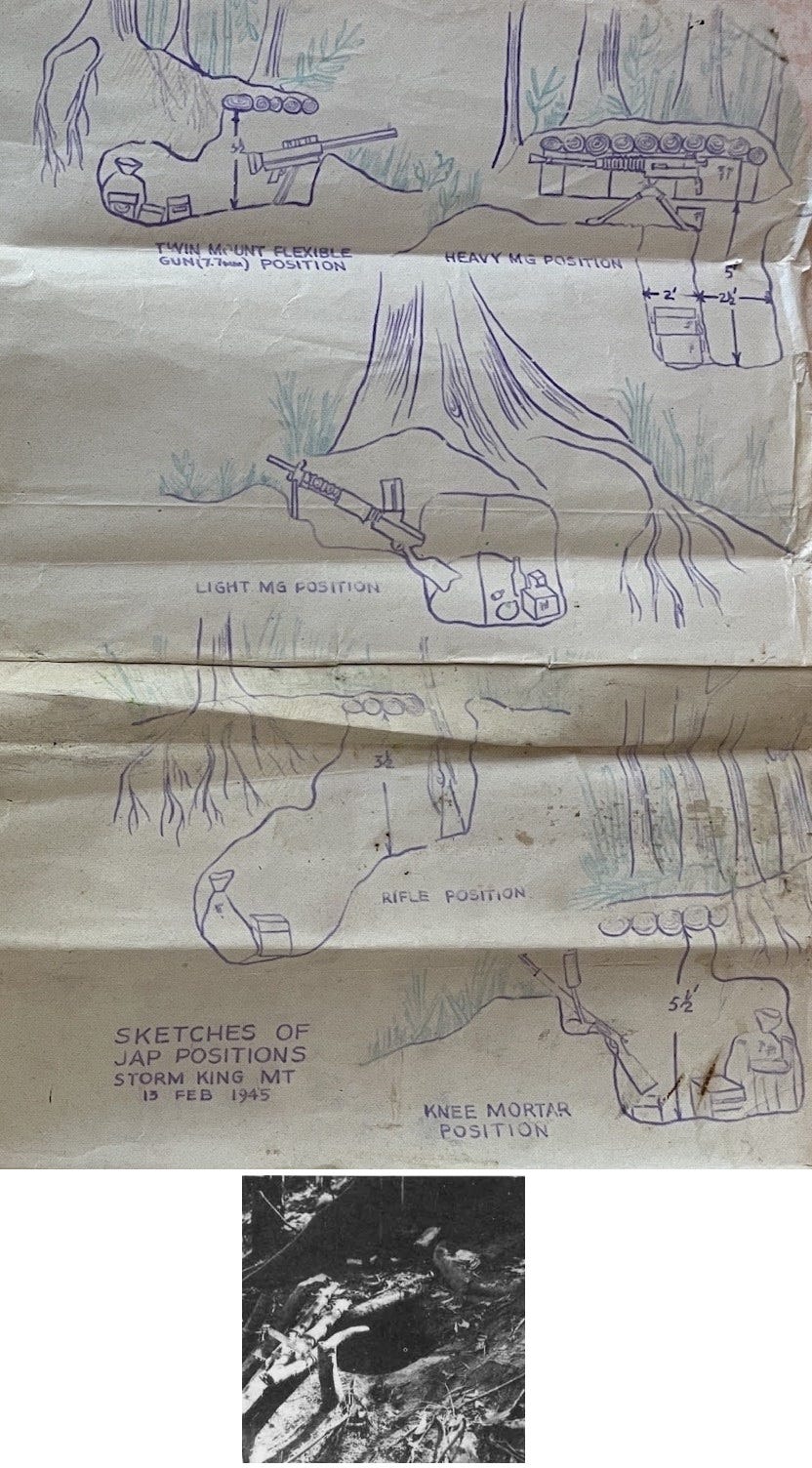

To take the ridges and destroy the naval guns, the 40th Infantry Division would have to attack Japanese troops occupying formidable fortifications. Japanese machine guns were emplaced in well protected positions deep in caves, with interlocking fields of fire, enabling them to rake approaching Americans with bullets while remaining almost invulnerable to the rifles, machine guns, and mortars of the infantry. The tunnels enabled Japanese troops to move unobserved to reinforce positions under attack. Every weapon in the division’s arsenal would be needed to knock out the Japanese machine gun positions one by one and reduce the underground fortress in the Bamban Hills.

The 160th Infantry Regiment’s 1st and 2nd Battalions began the assault on the ridges on January 24. M-10 tank destroyers with 76mm guns and M-7 self-propelled 105mm howitzers, protected by armor and able to fire high-explosive shells from long ranges, fired directly into the caves to knock out the naval guns and machine guns, clearing the way for the infantry to close in. Infantrymen then had to approach within a few feet of a cave’s entrance to finish off its defenders with hand grenades, demolition charges, and flamethrowers.

Four days of combat were needed before the 160th Infantry Regiment finally reached the peak of its ridge on January 28. The other ridge fell to the 108th Infantry Regiment the next day. With the Japanese barrier on the highway to Manila eliminated, the U.S. Army’s advance toward the Philippine capital could continue.

The end of the 40th Infantry Division’s first major fight of the war was only the beginning of a long, grueling battle in the mountains west of Manila. As most of the U.S. forces that had landed at Lingayen Gulf raced south toward Manila, the 40th Infantry Division continued attacking to the west into the Bamban Hills. Japanese forces surrounded in the area were determined to hold out in its rugged terrain, which they had ringed with fortifications.

The hills around Mount Pinatubo—famous half a century later for a 1991 volcanic eruption that killed more than eight hundred people, buried Clark Field in ash, and caused climate change worldwide—became a Japanese redoubt holding out on the long right flank of U.S. forces advancing on Manila. The 40th Infantry Division had to take hill after hill where Japanese troops had dug in, determined to resist as long as possible.

A fight for a peak named Storm King Mountain would occupy the 160th Infantry Regiment for more than a week. To reach it, they first had to take a promontory 300 yards away from the ridge that they had taken on January 28. The only way to approach the promontory was a narrow neck of high ground covered with thick jungle, no more than 75 yards across at its widest point, flanked by steep slopes that would be practically impossible to climb under fire.

In their way was a company of Japanese airborne troops from the 2nd Glider-Borne Infantry Regiment. These elite airborne infantrymen were dug into an array of well-prepared defensive positions: 150 rifle and machine gun pits covered with logs and earth and concealed by bamboo growing on top of them, or made by digging under the roots of large trees—each of them almost impossible to see, and difficult to destroy. Formidable firepower backed them: a 70mm field gun, three 90mm mortars, 17 light and 10 heavy machine guns, and 10 of the small but deadly Japanese grenade launchers that Americans called knee mortars.

The commander of the 1st Battalion, 160th Infantry Regiment, Maj. John McSevney, was killed at the start of the attack. McSevney was at the front line reconnoitering the Japanese defenses when a burst of machine gun fire suddenly hit and killed him. Lt. James Kim was standing only a few feet away from McSevney when he fell dead.

When the battalion moved forward, its men had to find the well-camouflaged Japanese positions one by one—almost always when the rifles and machine guns inside opened fire at them—and destroy the bunkers and the men inside them, all the time under fire from other positions in the Japanese defensive system. The fighting went on day after day, with the 160th Infantry able to move forward only a few dozen yards each day. Not until February 6, ten days after it began, would the attack finally succeed in crossing the 300 yards and reaching the top of Storm King Mountain.

The 160th Infantry advanced again on February 11, to attack another complex of fortified hills. Occupying the caves and tunnels of two 1,200-foot peaks called Scattered Trees Ridge and Snake Hill West were more elite Japanese troops, elements of the 2nd Glider-Borne Infantry Regiment and a unit of the Special Naval Landing Forces, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s marines. The 160th Infantry’s 1st Battalion attacked Scattered Trees Ridge and the 2nd Battalion moved on Snake Hill West, supported by artillery laboriously towed up Storm King Mountain and emplaced on its peak—155mm howitzers from James Kim’s old unit, the 222nd Field Artillery, and a 90mm antiaircraft gun. While the artillery blasted caves with direct fire, infantrymen moved forward to the cave mouths to eliminate the Japanese inside them with demolition charges.

James Kim, leading the 1st Battalion’s demolitions squad, captured the 160th Infantry’s first prisoner of war during cave clearing actions on February 11. Immediately after the explosion of a demolition charge in a cave, he rushed toward the cave entrance with his Thompson submachine gun raised and saw a Japanese soldier come out, firing his rifle. James killed him with a burst of .45 bullets, then saw another Japanese soldier stagger out of the cave. Acting on instinct, James moved toward him, ordering his men not to shoot and shouting in Japanese learned from the Army’s Japanese phrase book. When he got close enough he seized the Japanese soldier, who turned out to be badly wounded by the explosion, his eyes swollen shut and blood pouring from his ears and nose.

The wounded man gestured that he wanted to be shot, but James instead gave him water and had one of his men give him a cigarette. Inside the cave, they found only the dead bodies of Japanese soldiers killed by the demolition charge. Their captive was alive but could not see or walk, so James had him carried down the hill and taken to the rear for interrogation.

Under interrogation, the captured enemy soldier revealed valuable information about Japanese defensive positions in the area that helped the 160th Infantry to neutralize them and advance up the hills. James would receive a Bronze Star medal for taking the 160th Infantry’s first prisoner of war after an entire month of combat and making this intelligence windfall possible.

The 160th Infantry’s 1st and 2nd Battalions reached the peaks of Scattered Trees Ridge and Snake Hill West by the night of February 12. The 3rd Battalion then advanced southwest toward the regiment’s final objective, a fortified peak named Object Hill. Four days later, the 3rd Battalion secured Object Hill, and the regiment was finally able to stop and get some rest before the next phase of the attack into the Bamban Hills.

During the 160th Infantry’s battle on and around Storm King Mountain, the 108th and 185th Infantry Regiments moved forward to attack fortified hills on the 160th Infantry’s left and right. By February 19, they had secured their objectives, and the entire division could prepare for what its men hoped would be the final stage of the fight for the Bamban Hills.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.

Hi, saw this. Thank you for doing this. I live in this Town called "Bamban" where the 40th Division fought and libarate the town. I can help you if you want a file report regarding the atrocities happened here.