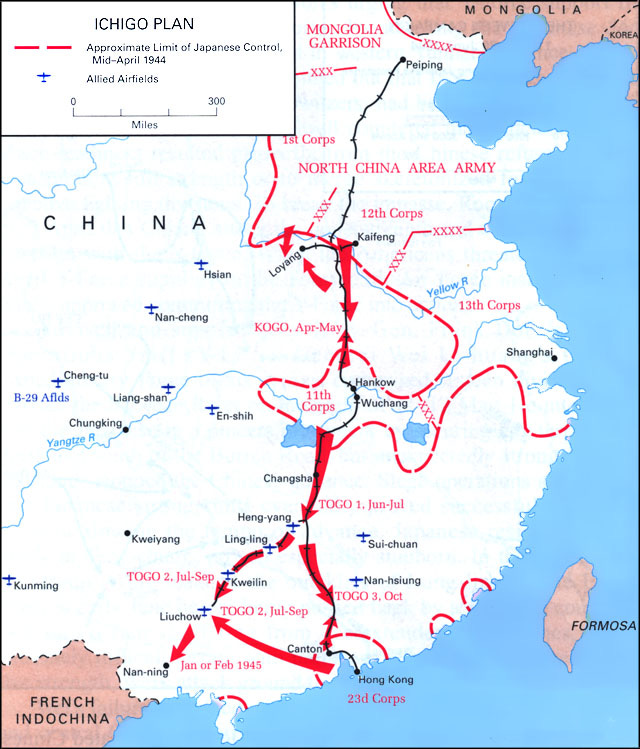

Peter and Richard Kim could not have chosen a worse time to leave Shanghai and try to make their way to free China. In May 1944, the Imperial Japanese Army was just beginning its largest land offensive of the entire Second World War, aimed first at the city of Changsha that was their planned destination. For the rest of 1944, Japanese forces drove south, capturing Changsha and the string of airfields that were the bases of the U.S. forces that Peter and Richard Kim hoped to join. Avoiding the rampaging Japanese army made their journey of 1,000 kilometers longer and more difficult than they could have imagined when they started.

Peter and Richard met the other members of their escape party at the Shanghai South railway station on May 10, 1944. They were following a plan put together by the leader of their group, Peter Chang, and one of Shanghai’s travel agents, who during seven years of Japanese occupation had developed networks for smuggling people to free China. Their cover story was that they were with a Chinese business relocating from Shanghai and Hangzhou to a town further inland, ordinary people only trying to make a living. To ensure safe passage on the Japanese-run railway, each person had a Japanese-issued certificate which allowed the bearer to travel freely within Japanese-occupied China, called a Pao Chia.

The escape party’s train trip from Shanghai to Hangzhou went uneventfully, and in Hangzhou, their leader Peter Chang took them from the train station to the office of a trading company located a few buildings away from the Hangzhou Confucius Temple, a historic landmark dating back to the 12th Century. There they met a merchant from free China who had sailed his boats to Japanese-occupied Hangzhou to trade tung oil for cotton, part of the black market exchanging goods between the territories controlled by the two enemy nations. The Imperial Japanese Army’s commercial organization in Hangzhou authorized the trade and allowed the boats to leave Hangzhou with their cargo of cotton and all 21 members of the escape party on May 19.

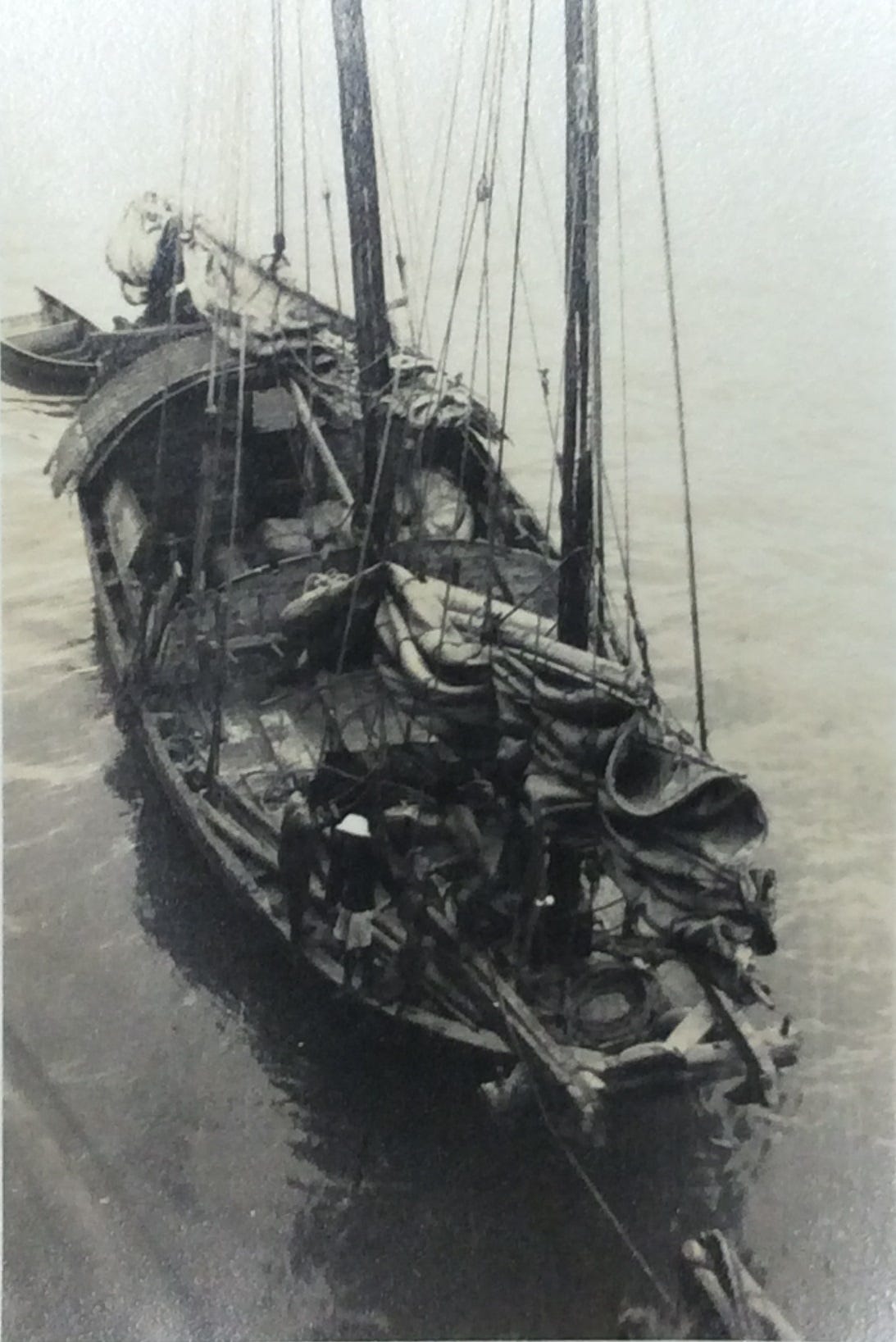

The convoy of wooden junks, propelled only by sails, moved slowly up the Qiantang and Fuchun Rivers past the last Japanese outpost at Fuyang and into no-man’s land, controlled by neither side’s army. They encountered numerous Chinese guerilla groups, some of them Chinese patriots who protected them, some of them outlaws and thieves who robbed them before letting them pass. On May 28, the merchant dropped them off and helped them to find trucks for hire to take them on the final overland leg of their journey to Changsha.

As the trucks moved toward Chinese-held territory, ponderously slowly using motors converted to run on gas from burning charcoal, news arrived that Japan’s Operation Ichigo offensive had begun on May 27. To avoid the Japanese battlefront advancing toward Changsha, the trucks headed south instead of west. Day after day they moved slowly along unpaved dirt roads until they were approaching Guangdong, one of China’s southernmost provinces. On June 4 they finally found a place to stop: the city of Shaoguan, the wartime capital of Guangdong, where the province’s Nationalist administration had relocated six years earlier when Japanese forces occupied the capital at Guangzhou in 1938.

Shaoguan offered the escape party a temporary refuge and a first opportunity to connect with the world that they were trying to reach. Peter found a telegraph office in Shaoguan with a line to Chongqing, more than 500 miles away, and used it to send a telegram to Walter Fowler, the U.S. official recommended to him by his friends at the Swiss Consulate.

Peter’s cryptic message to Fowler read, “Please radio Robert Biesel to notify Anker Henningsen that I am now enroute to Chungking via Hengyang and Kweilin. Essig sends regards. Peter Kim.” The series of names was a sort of code, intended to convey to this total stranger that someone named Peter Kim was coming from Japanese-occupied Shanghai and had numerous people to vouch for him: Fowler’s son-in-law Robert Biesel; Anker Henningsen, a U.S. official in Chongqing who was a close friend of Peter from prewar Shanghai; and Essig from the Swiss Consulate.

In Shaoguan, more than 200 miles from their intended destination, Peter and Richard also had a series of improbable encounters that made a successful end to their exodus from Shanghai seem tantalizingly close. These unlikely coincidences will be the subject of the next installment.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.