In the beginning, there was a family in Korea who had received word of a great nation on the far side of the world.

The father, Kim Chang Sei, and the mother, Lee Chung Sil, were Christians living in the Pyongyang area in the early years of the 20th Century. The city now known as the capital of North Korea was then the center of thriving communities of Korean Christians, started by American missionaries who had first arrived in 1895. American clergymen had made thousands of converts and founded churches all over the city and the region around it, creating one of the leading Christian communities on the mainland of Asia. By 1910, Pyongyang was home to more than 60,000 Christians and had become known as the “Jerusalem of the East,” renowned for the zeal of its converts and their eagerness to spread their new religion.

Along with their religion, Americans brought science and education to Korea. In a country regularly ravaged by epidemics of cholera and other infectious diseases and lacking a single modern hospital, American doctors sponsored by the churches contained the epidemics and built the first hospitals. Educational missionaries began the first schools open to the entire people of Korea, where previously only a few privileged families educated their children, using tutors teaching the Chinese classics. Their influence is visible today in Korea’s use of the unique hangul alphabet, created in the 15th Century by King Sejong of Chosun, which fell into disuse until the 1890s when Korean nationalists revived it and the American educational missionary Homer Hulbert founded Korea’s first western-style schools and taught hangul in them.

During this time the Empire of Japan conquered and colonized the country. Japan had invaded Korea and defeated Chinese forces to establish Japanese hegemony in 1894-1895, then eliminated Korea’s ruling monarchy, assassinating its queen and reducing its king to a puppet. A decade later, Japan fought and defeated Russia in a war for control of Korea, commonly called the Russo-Japanese War. On August 22, 1910, Japan formally annexed Korea, ending its existence as an independent nation.

Kim Chang Sei and Lee Chung Sil, married a month after the fall of their country on September 25, 1910, saw their destiny elsewhere. Raised by families of Christian converts and educated in American missionary schools, they had seen a glimpse of the American people and their ideals, enough to know that the United States of America was where they wanted to be.

International politics blocked their way, however, because the United States was then in a phase of its history when its western states opposed immigration from Asia. In 1907, the U.S. had made an informal agreement with Japan—never formalized in a treaty or a law enacted by Congress—to restrict emigration of Japanese subjects to the U.S. Koreans were among those subjects, and Japanese authorities would grant few exceptions to them.

The western profession of medicine offered them a path to America. Educated professionals were among the few people permitted to emigrate to the United States, and the colleges and medical schools that Americans had founded in Korea offered a chance to join the medical profession. In 1911, Kim Chang Sei enrolled in the medical school of Severance Hospital in Seoul, the first hospital in Korea, founded in 1885 by the American medical missionary Horace Allen. Lee Chung Sil enrolled in Ewha College, a school for women in Seoul founded by American Presbyterians in 1886, which later became one of South Korea’s most prestigious universities.

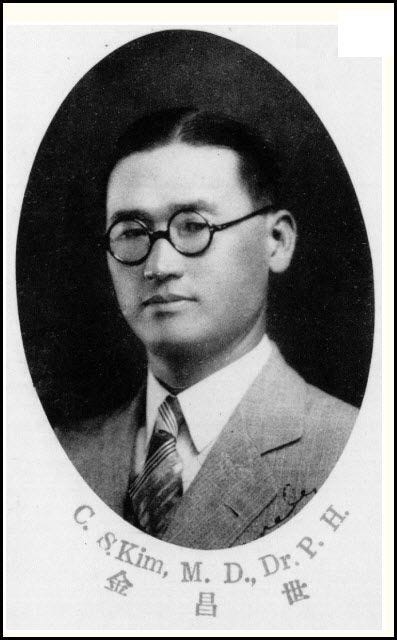

Kim Chang Sei graduated in 1916, after his medical school merged with Chosun Christian College to form a university that continues today as Yonsei University, one of South Korea’s leading institutions of higher learning. He was the class valedictorian, and he made the commencement ceremony memorable by making his address entirely in English, impressing the numerous American dignitaries in attendance. The moment is remembered in the annals of Yonsei University more than a century later.

The Kim family’s first children arrived while Kim Chang Sei attended medical school in Seoul and then returned to Pyongyang to practice medicine. Their first son Peter was born in 1912, then David in 1917 and William in 1919. Their parents gave them American Christian names, suitable for future Americans.

The opportunity to go to America finally came in 1920. After the family lived in Shanghai for two years while Dr. Kim practiced medicine at a Seventh Day Adventist hospital, specializing in tuberculosis and infectious diseases, the General Conference of Seventh Day Adventists sponsored him to go to the U.S. for further medical training. In November 1920, the family boarded a passenger liner and sailed to California with Lee Chung Sil pregnant with another child.

In Los Angeles she joined her sister Helen, who was married to a historic figure: Ahn Chang Ho, a founder of the Korean independence movement and also a leader of the nascent Korean-American immigrant community. Memorials bear his name in numerous places in Seoul and Los Angeles, as does the International Civil Rights Walk of Fame at the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site in Atlanta, which recognizes him as a leading contributor to the worldwide struggle for civil rights.

The family’s first American was born in Los Angeles in March 1921, a U.S. citizen by birth. His mother and father named him James. Another followed in April 1923, a daughter whom they named Betty Marie. Their son William unfortunately died at the age of only four, struck by a car on a Los Angeles street.

Kim Chang Sei pursued his graduate medical studies away from his family in Los Angeles. He started at the Adventist medical school in Loma Linda, California, then enrolled at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1922. In 1923 he enrolled in the Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health in Baltimore, the world’s first school of public health. Johns Hopkins awarded him his second doctorate in 1925, making him a Doctor of Public Health.

A wider world opened up to Dr. Kim Chang Sei after his graduation, as the new Doctor of Public Health embarked on a tour of Europe, North Africa, and South America to study public health conditions in a variety of nations around the world. He traveled by steamship to Sweden, Denmark, Italy, Greece, Egypt, Brazil, and numerous other countries, making new friends and connections during these travels.

In Sweden he met and befriended the Crown Prince, Gustaf Adolf. The future King Gustaf VI Adolf (1950-1973) was an intellectually curious man who in the years that followed would conduct archaeological excavations in Italy, Greece, and Korea and gain admission into the British Academy for his work in botany. The Crown Prince took a great liking to the visiting medical expert from Korea and America and gave him a tour of Stockholm, then traveled to Copenhagen with him.

Dr. Kim Chang Sei should have been on his way to fulfilling his desired destiny of becoming an esteemed member of the medical profession in the United States, and his wife and children headed toward bright futures as American citizens. The United States Congress had laid down a fateful mandate for them years earlier, however, and the barrier that it laid down would change the courses of their lives.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.