In 1924, Congress had passed a new Immigration Act that drastically reduced the number of immigrants allowed into the country and completely banned all immigration from Asia. The exclusion of Asians would last for more than 40 years (eased slightly during the Korean War in 1952), ending in 1965 when a new immigration law finally ended all racial preferences. The 1924 Immigration Act left the Kim family with no way to stay in the United States, even though they had two children who were born U.S. citizens. They had no choice but to leave the country after Dr. Kim Chang Sei’s student visa expired and to rebuild their lives somewhere else.

They returned to Korea in August 1926, crossing the Pacific in steerage, unable to afford better accommodation on a passenger liner. Dr. Kim returned to Chosun Christian College’s medical school to head a new department of public health, now the Department of Preventive Medicine at the Yonsei University College of Medicine.

Again a second-class subject of the Empire of Japan, he continued to look beyond Korea for his and his family’s future. Within two weeks of his arrival, he went to Beijing to participate in a public health conference sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation. In early 1928 he again moved to Shanghai, accepting a position as field director of the Council on Health Education, an American organization spreading knowledge of modern medicine in China. The family followed in August, and they moved into a house in Shanghai’s French Concession, a district located in a long strip of land south of the International Settlement.

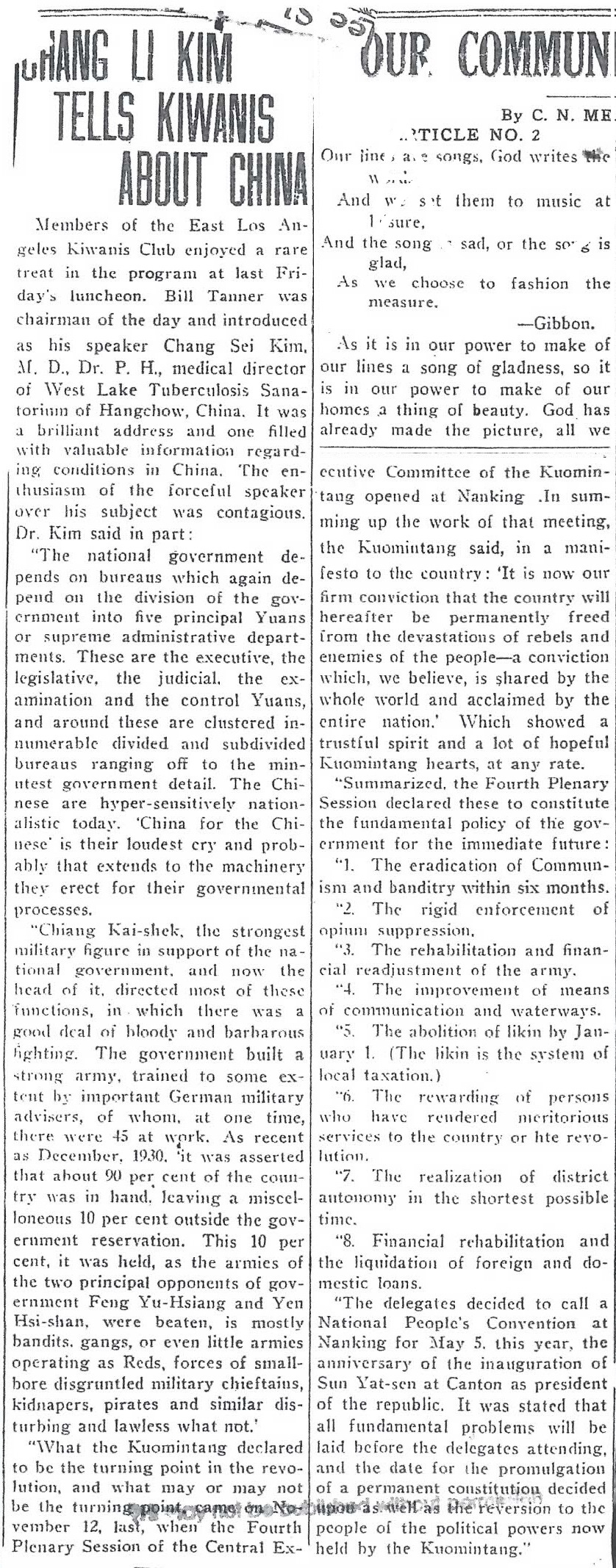

From his professional base in Shanghai, Dr. Kim traveled all over China and elsewhere in Asia. He lectured on public health at Peking Union Medical College, a medical school in Beijing supported by the Rockefeller Foundation, and the medical school of Lingnan University in Canton (now Guangzhou). He went to Hangzhou to build a tuberculosis sanitarium, then spent several months in the Philippines, a U.S. territory, to found a tuberculosis sanitarium in Baguio, the summer capital of the U.S. Governor-General.

The Kim family grew further during these years. In June 1927 in Seoul they had another son, whom they named Richard. In Shanghai in 1929 Lee Chung Sil found herself pregnant again. In January 1930, another son was born. His parents named him Arthur.

Dr. Kim Chang Sei was not present for Arthur’s birth because he had again gone to the United States. He had accepted an invitation to participate in a medical conference in New York, and his visit resulted in an offer to stay in the U.S. to conduct research for the National Tuberculosis Association, an organization which still exists as the National Lung Association. His research continued to the end of 1930, then into 1931, and his visit to the U.S. eventually became a period of residence lasting for years, with stays in California, Baltimore, and New York.

Bringing the family to the United States was always his hope, and it became urgently necessary in 1932. The Imperial Japanese Army had invaded and occupied Manchuria in 1931, and in January 1932, Japanese troops, warships, and aircraft attacked Nationalist Chinese forces in Shanghai, starting a battle for the city that lasted two months. Thousands of civilians died and many more became homeless as the fighting raged across Shanghai. A Japanese manhunt for Korean independence activists began in April 1932 after one group detonated a bomb at a Japanese victory ceremony in Shanghai, killing or wounding many of Japan’s senior military commanders and civilian officials in the city. Ahn Chang Ho was one of those arrested, and his sister in law Lee Chung Sil was another prime target.

Lee Chung Sil and her six children evaded arrest thanks to American friends, the McNair family. She and her eldest son Peter were close friends of Mrs. McNair and her eldest son, Roy McNair, Jr. As Americans, the McNairs could refuse to cooperate with Japanese police, and they protected Lee Chung Sil and her children at their house at 49 Route Winling (now called Wanping Road) until the Japanese dragnet came to an end and it was safe for the Kims to return to their own house.

With the lives of his wife and children now at stake, Dr. Kim Chang Sei invoked all of the professional connections in the United States that he could in an effort to secure visas for them. Letters of recommendation from leaders of the Rockefeller Foundation, the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, and the National Tuberculosis Association went to the U.S. consulate in Shanghai in support of an application for a temporary visitor visa by Lee Chung Sil in June 1932. None of the support made a difference. The U.S. consul refused her application.

Kim Chang Sei also tried to help Ahn Chang Ho by persuading members of Congress to pressure Japan for Ahn’s release from captivity. In early May 1932, he went to Washington and met members of Congress including Senator William Borah of Idaho, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and Representative John Linthicum of Maryland, chairman of the House Foreign Relations Committee. His efforts were fruitless, and Ahn’s imprisonment continued with no official U.S. statement against it.

Powerless to help his family or Ahn Chang Ho, Kim Chang Sei continued to live alone in the United States. His work continued for another year, taking him from California to New York, where he established a medical facility in downtown Manhattan’s Chinatown and served as the health commissioner for the Boy Scouts in Manhattan.

In February 1934, everything suddenly seemed to change when a telegram arrived at the family’s house in Shanghai. It was from their father in New York, and it announced that he had finally worked out a way for them to enter the United States to join him, and Peter was to be enrolled in the Horace Mann School, an exclusive college preparatory school in New York. The family joyfully prepared to depart Shanghai and return to the United States in March until another telegram arrived from New York. Their father had committed suicide, and he had done it on March 15, 1934, the birthday of his American born son James.

The family would never learn why their father had taken his own life. Far away in Shanghai, all that they knew for certain was that he had unexpectedly committed suicide by inhaling oven gas in his apartment. Even a brother in law who also lived in New York, a block away from Columbia University in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, had been taken by surprise.

Perhaps he had worked out an arrangement to bring them to America, and it had fallen through, plunging him into despair. Perhaps the arrangement and the enrollment of his son Peter at the elite Horace Mann School in New York had been no more than fantasies, the last desperate thoughts of a man overwhelmed by feelings that he had failed his distant family whom he had not seen for years. Newspapers stories about his death reported threats against him and attempts at extortion, indicating that something had gone wrong with his life in New York. His wife and children would never know for certain.

Dr. Kim Chang Sei’s suicide left Lee Chung Sil and her six children Peter, David, James, Betty, Richard, and Arthur stranded in Shanghai. They were Americans in spirit but would have to grow up far from the country that they considered to be theirs, in the American community of Shanghai.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.