The MS Gripsholm, WWII Mercy Ship

From 1942 to 1946, the Swedish passenger liner MS Gripsholm served the United States as a mercy ship, with the special task of transporting civilians of the Allied and Axis nations for repatriation to their home countries. Chartered by the U.S. government and flying the flag of neutral Sweden, the Gripsholm made 12 voyages across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, safely transporting 27,712 passengers in exchanges of civilians by the combatant nations. The ship’s service to the United States demonstrated the contributions of diplomacy and neutral nations in a world war and was a remarkable episode in maritime history in which Peter Kim played a part.

Built in 1924, the 18,000-ton Gripsholm was a landmark ship design as the first diesel-powered transatlantic liner. The ship served for its first 15 years as one of the premier passenger liners of the Swedish American Line, primarily serving the Gothenburg to New York route, with many voyages also calling at Halifax, Nova Scotia.

The Gripsholm also sailed into the Indian Ocean for the Swedish American Line’s winter cruise service to the Mediterranean and the tropics, which began in 1927. This map shows the course of the Gripsholm’s 1934 winter cruise, which took vacationers through the Suez Canal and around the Indian Ocean, with port calls at Bombay, Colombo and Zanzibar.

The Swedish American Line suspended passenger service after the outbreak of World War II in Europe in September 1939, and its liners took on new roles as mercy ships after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The U.S. government chartered the Gripsholm and the older steam-powered liner Drottningholm for the special task of conducting exchanges of civilians of the Allied and Axis nations, for repatriation to their respective countries. The Drottningholm served under U.S. charter for two voyages to Europe and back in 1942 before the United Kingdom took over its services. The Gripsholm served the United States from June 1942 to 1946 under a U.S. Department of State charter managed by American Export Lines, a shipping company with operations throughout the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf.

At a time when warships and merchant vessels alike were painted grey or in camouflage and sailed blacked out at night, the Gripsholm traveled as conspicuously as possible to ensure that it would be recognized by both sides. Painted white with large stripes in blue and white Swedish colors, and with GRIPSHOLM, SVERIGE and DIPLOMAT in huge letters on each side of the ship, the Gripsholm sailed at night with lights blazing to illuminate the ship and the names on its sides. These measures proved effective, as the ship was never attacked accidentally by German U-boats or any other Axis or Allied combatants.

In its voyages to repatriate American and Japanese civilians, the Gripsholm sailed from New York to the Indian Ocean to meet Axis country-flagged ships at neutral ports. On its first voyage, the Gripsholm left New York on June 18, 1942 with 1,083 Japanese civilians, then took on another 417 in Rio de Janeiro before crossing the South Atlantic and rounding the Cape of Good Hope. At the port of Lorenco Marques in Portuguese Mozambique, the ship rendezvoused on July 22, 1942 with the Japanese liner/troopship Asama Maru, with 871 Allied county civilians released from detention in Japan, Korea, Southeast Asia and the Philippines, and the Italian Far East Line’s Conte Verde, with 639 civilians from Shanghai, whose selection and departure Peter Kim had administered. A total of 1,510 boarded the Gripsholm for their journey home, almost completely filling the ship’s accommodations for 1,557 passengers.

The Gripsholm ‘s second mission embarked from New York on September 21, 1943, bound for Mormugao in Portuguese India, a small coastal enclave near Goa that was neutral Portuguese territory surrounded by the British Indian Empire. In Mormugao the Gripsholm met the Japanese naval transport Teia Maru, a French passenger liner that the Japanese had seized in Saigon. The ships again exchanged approximately 1,500 Japanese civilians for 1,500 Americans, Canadians and other citizens of North and South American countries. Almost 1,000 of them were from Shanghai, now liberated from the internment camps that the Japanese had forced them into in early 1943. Peter Kim, now working for the Swiss Consulate in Shanghai, had again organized their departure. The Gripsholm returned to New York with its American and Canadian repatriates on December 1.

In 1944 the Gripsholm stayed in the Atlantic, making three voyages to Europe for exchanges of civilians and prisoners of war with Germany. The ship called at the neutral ports of Lisbon, Barcelona, and the ship’s home port of Gothenburg, where it exchanged German civilians and prisoners of war for American diplomats, other civilians, and prisoners of war.

In 1945 the Gripsholm returned to the Indian Ocean for exchanges with Japan. The ship went on four missions in 1945, again rescuing missionaries, businessmen, journalists and others who had been held in terrible conditions in Japanese prison camps, now after two further years of captivity.

After the war the Gripsholm continued in U.S. service into 1946 to make three further voyages to repatriate civilians and prisoners of war. A February 1946 voyage to the Mediterranean was unusual in transporting several hundred prison inmates for deportation to Italy and Greece, including the famous gangster Lucky Luciano.

Between voyages, the Gripsholm spent long periods docked in the New York area for refitting. After the 1942 voyage, the ship sailed up the Hudson River to dock in Yonkers, New York, likely the reason for it passing under the George Washington Bridge in this photo. During other periods it docked in Jersey City, New Jersey. The Swedish crew were officially considered to be with the U.S. Merchant Marine and received the same shore leave privileges given to sailors who were U.S. citizens. Like the ship, they spent years continuously abroad. Hired under six month contracts in 1942, the original crew served through 1944, and many continued to the end in 1946.

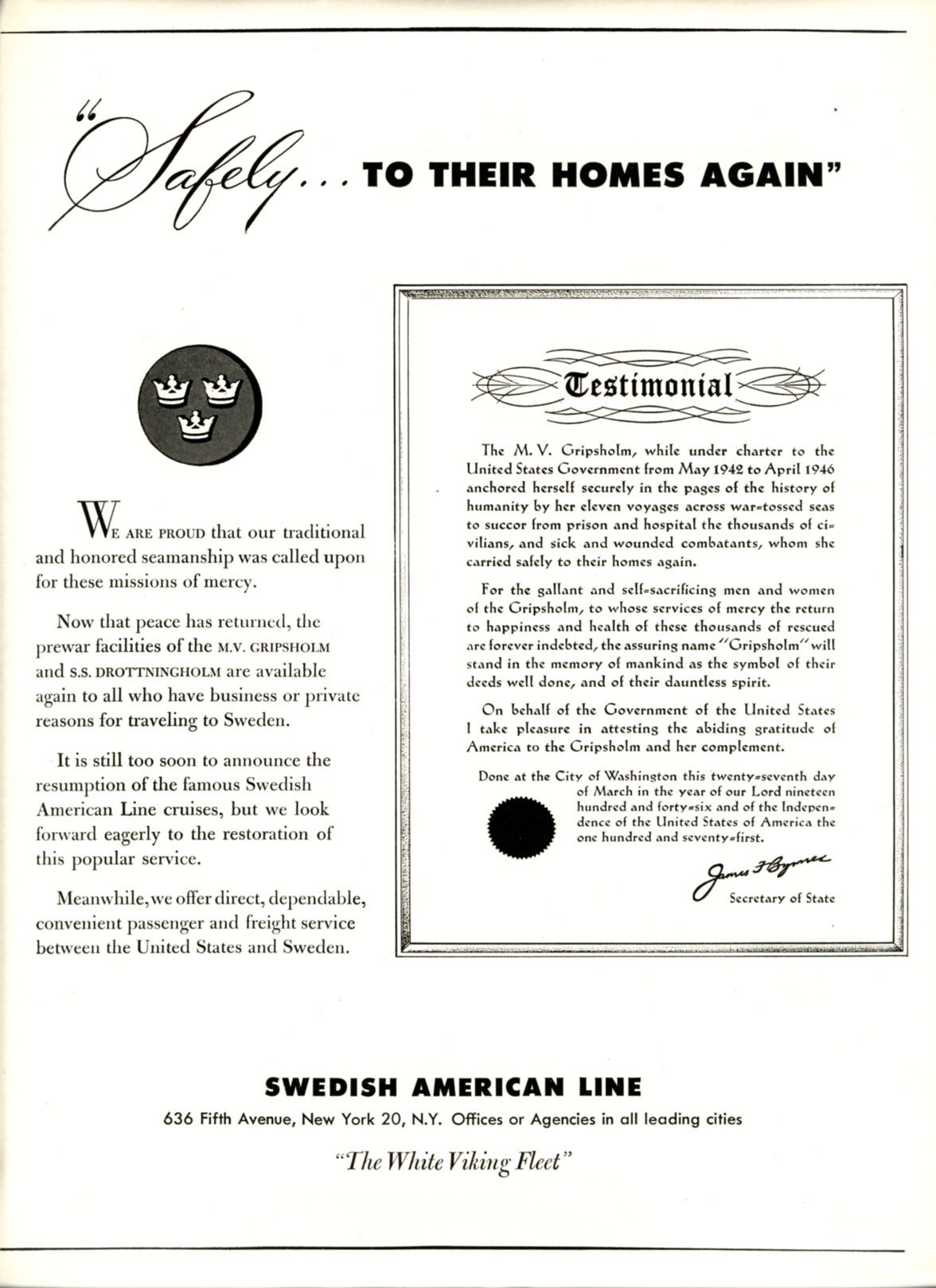

The ship and its crew were acclaimed for their service during and after the war. The arrival of the Gripsholm in New York was always a newsworthy event, widely covered in newspapers and newsreels. After the war, the U.S. government officially thanked the Gripsholm and its crew, with the Secretary of State sending an official letter of commendation and the entire crew receiving the U.S. Merchant Marine Victory Medal in recognition of their exceptional wartime service.

At the end of its service to the United States in 1946, the Gripsholm resumed its passenger service with the Swedish American Line before being sold in 1954 to a German shipping company. Renamed MS Berlin, the ship became Germany’s first postwar transatlantic liner, serving a transatlantic route from Bremerhaven to New York and Halifax.

As the Berlin, the ship again became the passage to a better life for many people, this time for Germans and other Europeans immigrating to the United States and Canada. From 1955 to 1966, the ship arrived 33 times at Pier 21 in Halifax (shown), the immigration and customs facility that was the Ellis Island of Canada from 1928 to 1971.

The Gripsholm finally came to an end in 1966 when the 42 year old ship was scrapped, but it has lived on in spirit in an unusual way. In 2012, the government of Canada selected a photograph of the ship visiting Pier 21 as MS Berlin to serve as the central image of Canada’s ePassport, representing Canada’s history of welcoming immigrants. Millions of people traveling the world carrying the Gripsholm‘s image is a fitting tribute to this remarkable ship and all of those who contributed to the success of its wartime voyages.

All images except for the final image from Canada’s ePassport are from the website A Tribute to the Swedish American Line, https://www.salship.se/, and its page on the Gripsholm and Drottningholm, https://www.salship.se/mercy.php.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.

Thank you Richard! My grandparents were on the 1942 voyage out of China.