During the Second World War and the Korean War, a family from Korea completed an extraordinary journey from Asia to the United States of America that would make four of its sons pioneers in U.S. Army intelligence, the Army Special Forces, and the Central Intelligence Agency. Their story, hidden for most of a century, will be told for the first time in my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

The story of the Kim family began in Pyongyang in 1910, just after the Empire of Japan annexed Korea, when a young man named Kim Chang Sei married Lee Chung Sil. From families of early Korean converts to Christianity and educated in American missionary schools, they decided that they would find a way to leave their conquered and colonized homeland and go to the United States, where they would become American citizens and raise their children as Americans. Kim Chang Sei, a brilliant scholar who learned and mastered the English language in Korea, became one of Korea’s first medical doctors as a member of the first graduating class of the medical school of Yonsei University in Seoul.

Kim Chang Sei and Lee Chung Sil brought their growing family to the United States in 1920. Already with two sons, Peter and David, they had two more children in America, James and Betty, born U.S. citizens. Kim Chang Sei became a leading expert in the U.S. on combating tuberculosis, malaria, and other infectious diseases, seemingly on his way to becoming a U.S. citizen himself.

The American dream of the Kim family died when Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924, which banned immigration from Asia. Forced to leave the country, they first returned to Korea, then moved to Shanghai, where they could live as part of the international city’s American expatriate community and raise their children as Americans. There they had two more sons, Richard and Arthur. Kim Chang Sei returned to America in 1930 as a visiting medical researcher and tried to find a way to bring his family with him, but as time passed without success, he struggled with his mental health and committed suicide in 1934.

The children of Kim Chang Sei and Lee Chung Sil proved to be completely and unshakably loyal to the United States and their fellow Americans in Shanghai after the Empire of Japan attacked the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor and occupied the Shanghai International Settlement in December 1941. During the long war that followed, each found his or her way to resist and fight back against the empire that had gone to war with the country that they considered to be theirs. After victory over Japan in 1945, the grateful commanding officers of the U.S. Army in China began a campaign to admit them into the United States and make them U.S. citizens.

Peter, the eldest son, became the protector of American citizens in Shanghai, then their liberator, after Japanese occupation authorities confined White citizens of the Allied nations in internment camps. He worked for the neutral Swiss consul in Shanghai to monitor conditions in the internment camps and administer Red Cross aid, then in the summer of 1944 escaped Shanghai with his younger brother Richard. Enlisting in the U.S. Army in free China, he became the leading expert on Japanese-occupied China for Army intelligence. When the Emperor of Japan announced his decision to surrender, the Army high command in China selected Peter Kim as a leader of the intelligence mission to Shanghai to liberate the internment camps.

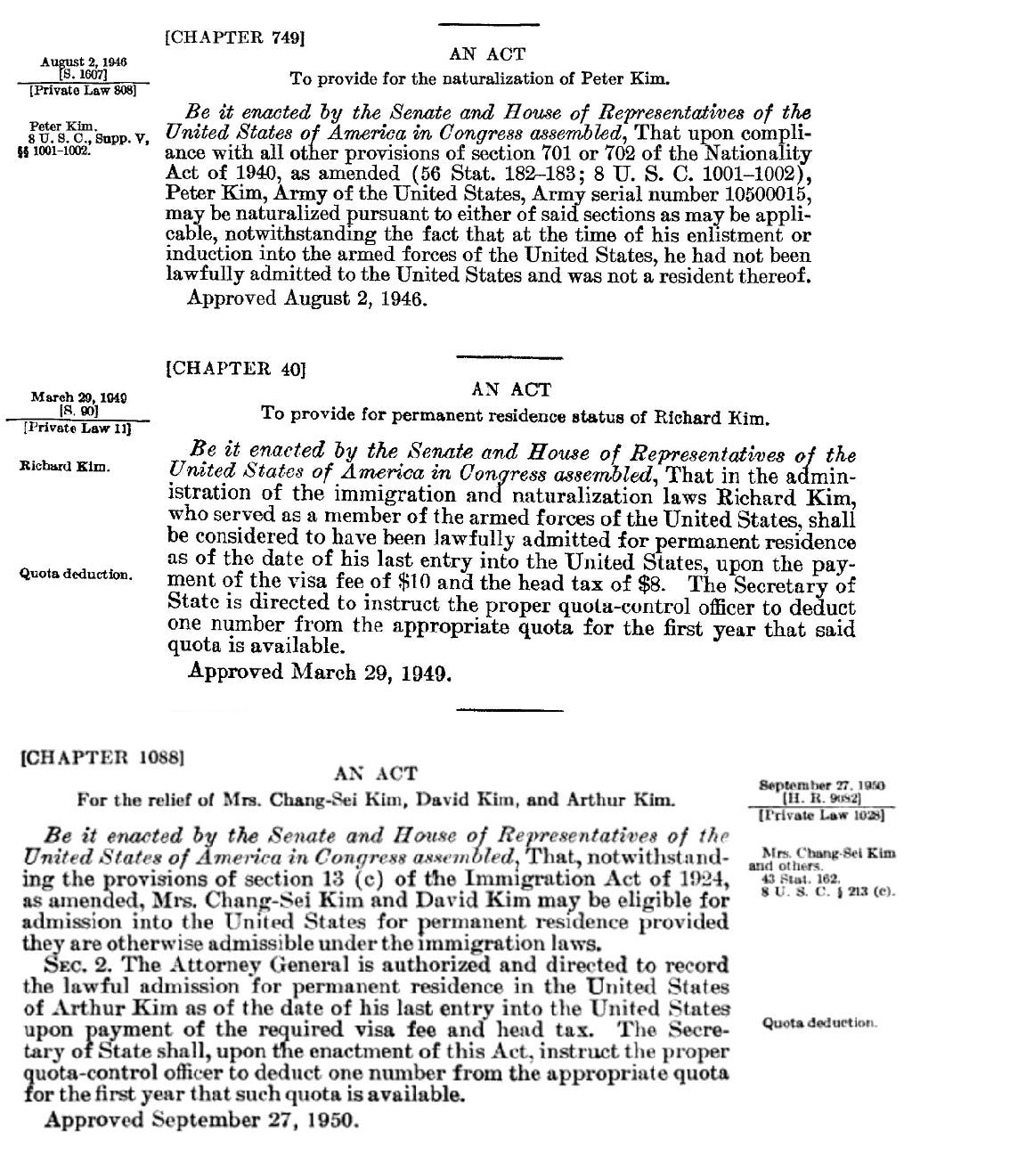

Peter Kim’s extraordinary actions in Shanghai in August 1945 motivated the U.S. Army’s senior commanders in China to lobby Congress to pass a Private Law granting him U.S. citizenship. The success of this effort in August 1946 led to two further acts of Congress legally admitting the rest of the family into the United States in 1949 and 1950.

James, born a U.S. citizen, was in California in 1941 and had enlisted in the U.S. Army three months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. After successfully resisting categorization as a Japanese-American and consignment to an internment camp, he excelled as a soldier and was selected to become an infantry officer. Deployed to the Pacific, he led an infantry platoon in combat against the Imperial Japanese Army in the Philippines in 1945. A college student at Georgetown University at the start of the Korean War, he led the lobbying campaign for the 1950 law that admitted his remaining family members into the U.S., then was called up for active duty in Korea. His assignment was to the recently formed CIA, where he would serve for a quarter century and become the first Asian-American promoted to a senior leadership position in the agency in the early 1960s.

Arthur served as a U.S. Army intelligence asset in Shanghai as a 14 year old in 1944, collecting intelligence in the Japanese quarter of Shanghai. When the Korean War began he tried to enlist in the U.S. Army in California but was turned away as a foreign student, and he traveled all the way to Hawaii to find a draft board willing to draft him. He served in Army intelligence in Korea and then was recruited into the CIA.

Richard enlisted in the U.S. Army in Kunming, China in December 1944 and returned to Shanghai as a sergeant with the U.S. forces in the city in September 1945. After the war he went to high school and college in the U.S. on the GI Bill, and he ended up back in the Army after enlisting in the National Guard to help pay for college and getting called up for active duty during the Korean War. After the Korean War he decided to stay in the Army to join the recently formed Special Forces, in which he served in Germany and during the Vietnam War. In 1971 he retired as a lieutenant colonel for a new calling as an Episcopalian minister.

The journey to America of the Kim family was an extraordinary episode in the history of the American people and their military and intelligence services. The publication of Victory in Shanghai in 2025 will reveal their full story for the first time, and in the meantime, this Substack series will introduce parts of it to the public.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.