The 40th Infantry Division, relieved of the task of being the first to fight in the invasion of Japan, instead became part of the U.S. forces that liberated Korea. On August 22, the division received orders to join the Army’s XXIV Corps, whose three infantry divisions were preparing to embark from Okinawa to occupy Korea south of the 38th Parallel.

The division rushed to reorganize and to prepare to leave their base on Panay for the long sea voyage to Korea. Its 108th, 160th, and 185th Infantry Regiments reorganized from Regimental Combat Teams into Regimental Military Government Teams, which would replace the Japanese colonial administration in Korea and govern until new Korean institutions could emerge. Their personnel received briefings on what little knowledge of Korea the U.S. Army possessed. On September 7, the first amphibious transport and landing ship tank (LST) convoy departed Panay. More convoys followed until October 5 to complete the sealift of the division’s 14,389 soldiers.

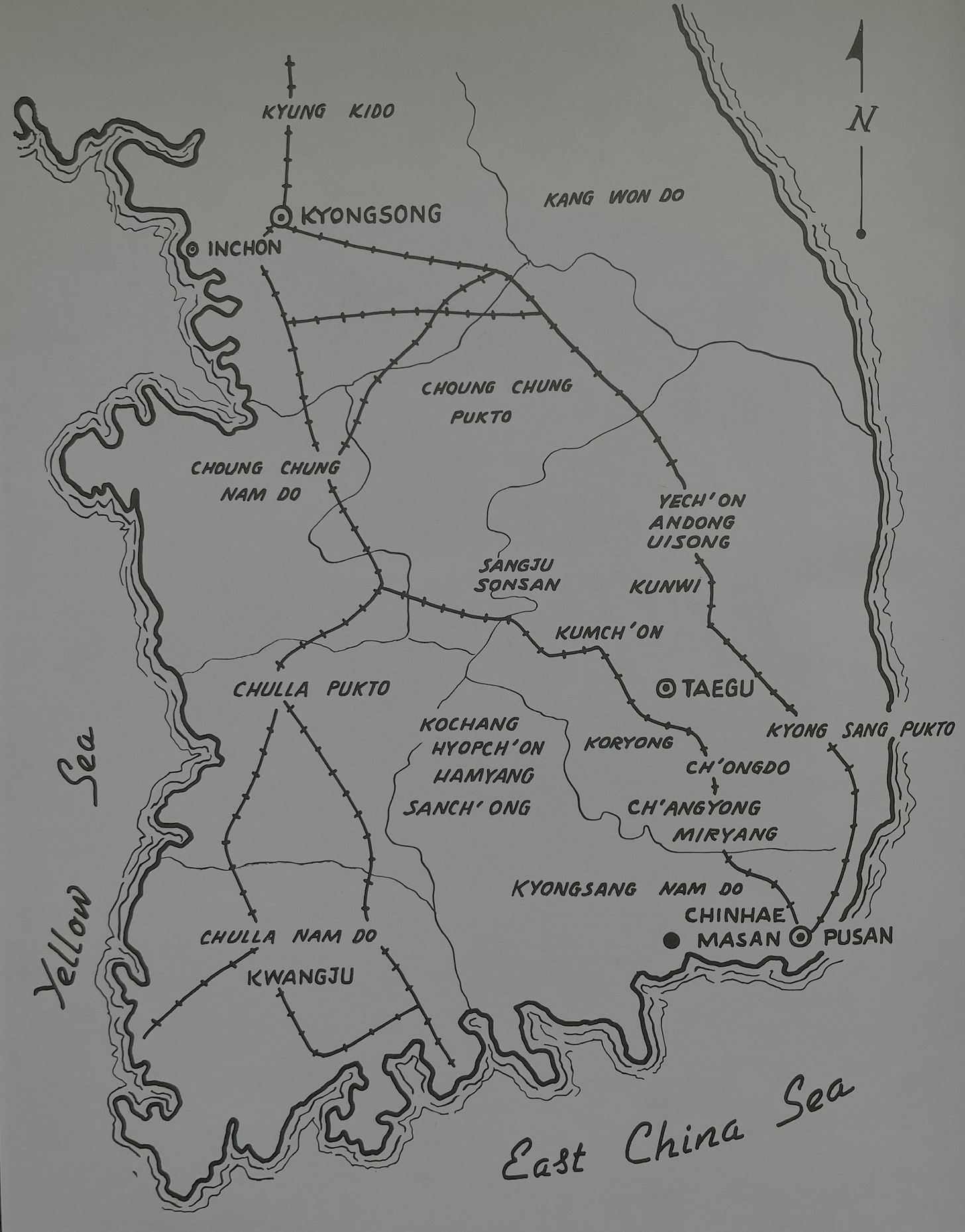

As the last of four U.S. Army divisions to arrive in Korea, the 40th Infantry was destined for the most distant area from the U.S. landing site at Inchon: the port city of Pusan. The advance party went ashore at Inchon on September 15 and then moved overland to Pusan by railroad. By October 2, the entire 160th Infantry Regiment and supporting units had arrived in Pusan, as the 108th and 185th Infantry Regiments spread out across the rest of the southernmost part of the Korean peninsula from Taegu in the east to Kwangju in the west.

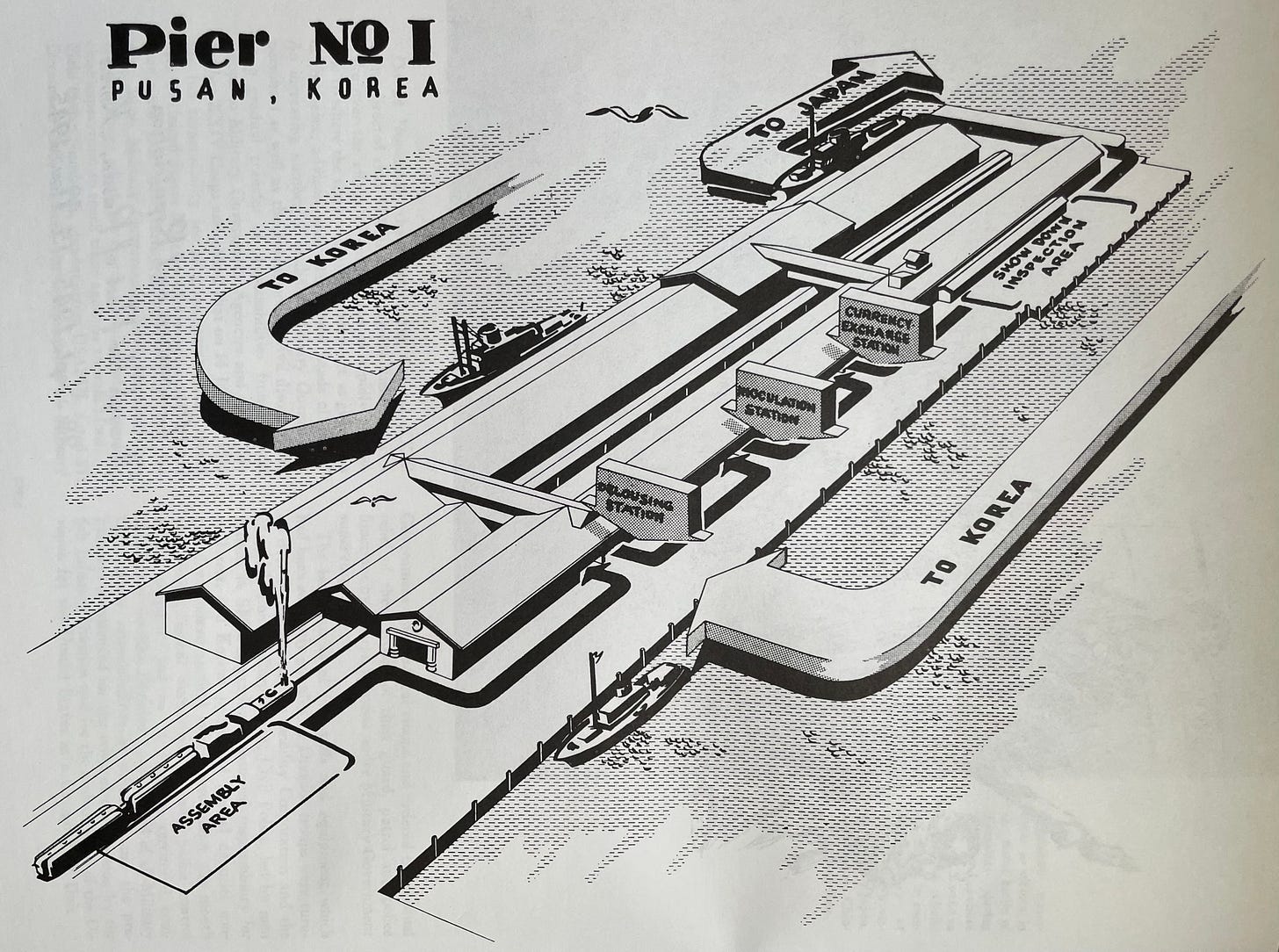

The 160th Infantry Regiment’s initial mission in Pusan was one of the most consequential in immediate postwar Korea: handling the departure of Japanese military personnel and civilians from Korea, and the return of Koreans from Japan—hundreds of thousands of people moving each way, through a single pier on the Pusan waterfront.

The first evacuation ships departed on September 26, with 3,675 Japanese soldiers and 5,341 civilians on board. By the end of the first week, 23,843 soldiers and 17,413 civilians had been embarked. All Japanese troops were cleared from the 40th Infantry Division’s sector by October 5, and the evacuation of Japanese soldiers from other areas of Korea continued until November 1. The repatriation of Japanese civilians went on even longer into December.

A total of 394,089 Japanese soldiers and civilians passed through the care of the 160th Infantry Regiment in Pusan by December 19.

Going the other way, 482,193 Koreans returned from Japan to their native land through Pusan.

The 160th Infantry Regiment’s veteran soldiers and recently arrived replacements handled the task of supervising the evacuations and arrivals efficiently and humanely, ensuring that the vast movement of people went in an orderly manner and peacefully despite many years of pent-up hostility between Koreans and the defeated Japanese.

While elements of the 160th Infantry Regiment administered the vast movement of people through Pusan, all three of the 40th Infantry Division’s Regimental Military Government Teams delved into the task of administering their regions of Korea. They tried to mediate between the bewildering array of factions—more than 100 political parties across Korea—that emerged suddenly in the excitement of liberation from Japanese rule. Predominant among them were the nationalists of the Korean Provisional Government, founded in 1919 in Shanghai under the leadership of Ahn Chang Ho, the uncle-in-law of Lieutenant James Kim of the 160th Infantry Regiment.

It is likely that no one in the 40th Infantry Division or the entire American Military Government in Korea knew that a U.S. Army officer in Pusan was a close relative of one of the founders of the Korean Provisional Government, whose successors would eventually found the Republic of Korea. James Kim had been with the 40th Infantry Division since it was a National Guard outfit guarding the California coast in the first days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Aside from his last name, there was nothing identifying him as Korean. He did not even speak the Korean language, which his family had not used during his childhood in Los Angeles and Shanghai. Korea was as foreign to him as it was to any other GI.

Every day in Korea was another day that James knew his family was tantalizingly close but still seemingly a world away. Eight years earlier, he had left them in Shanghai. Now, after his four-year journey across the Pacific with the U.S. Army, he was only five hundred miles away from Shanghai. But there was no possibility that his unit would get sent there, and he had no way to contact his family in Shanghai to find out how they were doing or even to learn whether they were still alive.

Veteran soldiers who had earned enough points under the Army’s system for determining eligibility for discharge were constantly leaving to return stateside. More than 1,100 men left the 40th Infantry Division before its advance party even landed in Korea, replaced by only half as many new recruits. Thousands more went home each month. By mid-January 1946, the division had fewer than 7,000 officers and enlisted men, half of its strength five months earlier.

Lt. James Kim, with four years of service and Bronze Star and Purple Heart medals earned in combat, qualified for discharge but did not want to return to the U.S. His family was in Shanghai, so he would have to find another way home.

He had no idea that while he was biding his time in Korea, his older brother Peter was already in Shanghai as one of the key leaders of the liberation of the city and its imprisoned foreign community by the U.S. armed forces and intelligence services.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.