The 40th Infantry Division was chosen to be the first unit in the entire U.S. Army and Marine Corps to fight in the invasion of Japan. Training for this last terrible mission of the war began in earnest at the beginning of July 1945.

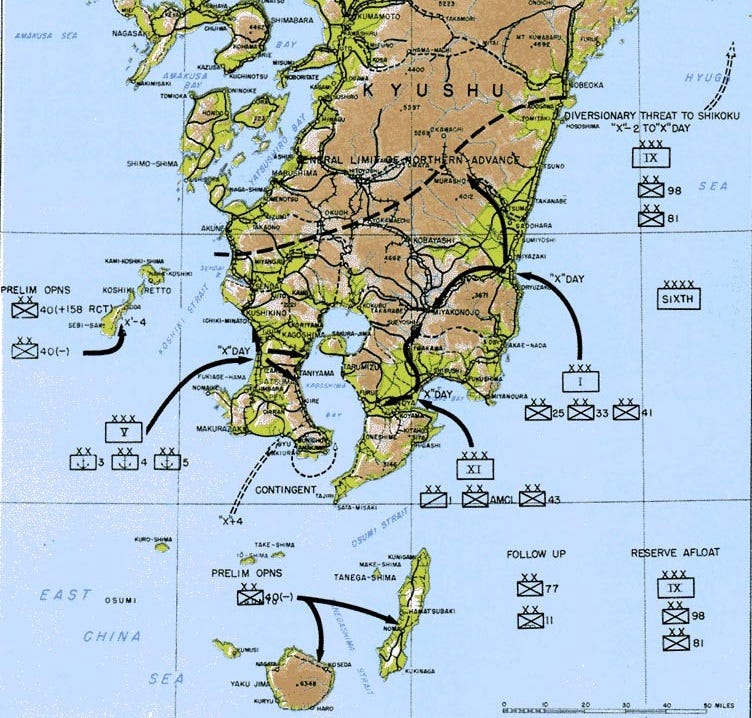

Operation Downfall was the name of the planned invasion of Japan, which would unfold in two enormous amphibious assaults. First, in Operation Olympic, U.S. forces would attack the southern island of Kyushu to draw in Japanese forces and secure staging areas and airfields for the next phase. “X-Day,” the date when the invasion would begin, was scheduled for November 1, 1945. Months later, in Operation Coronet, U.S. forces would invade the central island of Honshu and surround and conquer Tokyo. This climactic battle would not come until March 1, 1946, at the earliest.

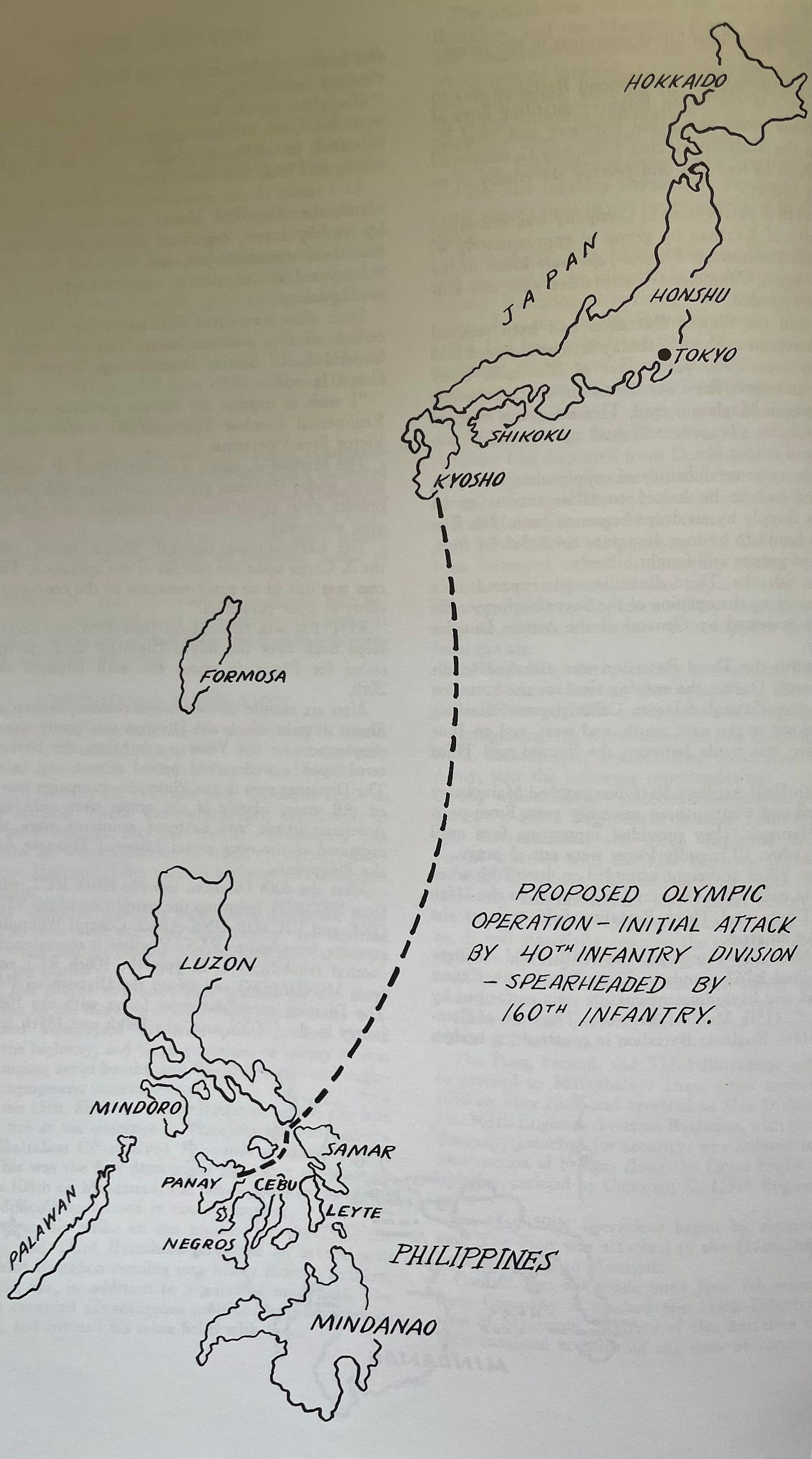

The 40th Infantry Division would be the first Army or Marine division to go into action. Four days before X-Day, the 40th Infantry would attack and secure two groups of islands off the coast of Kyushu that lay astride the sea-lanes to the invasion beaches. The mission required a unit with the experience to execute an amphibious operation reliably and then quickly eliminate Japanese defenses. After conducting successful amphibious landings on Luzon, Panay, Negros, and Mindanao, and overcoming Japanese troops dug into formidable fortifications in the Bamban Hills and at Dolan Hill, the 40th Infantry Division was as ready as any unit for the mission.

The invasion of Japan was to be the largest amphibious operation in the history of warfare, against a still-formidable enemy fighting to defend their homeland. Three quarters of a million U.S. soldiers and Marines would fight on Kyushu in Operation Olympic and more than a million in the siege of Tokyo in Operation Coronet. Opposing them were Japanese forces that still numbered more than four million men, with thousands of tanks and artillery pieces. Millions more Japanese civilians were being hastily trained and armed to fight in the last-ditch defense of their country. Thousands of kamikaze aircraft, suicide attack boats, and other weapons of the Divine Wind Special Attack Units waited to strike at the U.S. fleet as it approached Japanese waters and then floated offshore to support the ground forces.

Massive casualties were expected in the upcoming campaign. An estimate from the Pentagon in June 1945 was that about 200,000 U.S. servicemen would be killed or wounded in the invasion of Japan. General MacArthur’s staff projected that more than 100,000 casualties would occur in Operation Olympic alone. These figures, no more than rough guesses, would be dwarfed by the scale of Japanese military and civilian deaths, which were likely to number in the millions.

The soldiers of the 40th Infantry Division did not need any official announcements to understand the grim task ahead of them. They had experienced how ferociously Japanese soldiers could resist when isolated thousands of miles from home in a hostile country and with limited weapons and ammunition and even food to eat. Supposedly weak and beaten Japanese units had stopped and bloodied them at Storm King Mountain and on Dolan Hill. Now they was going to have to fight millions of Japanese soldiers in the mountains and cities of their own country, backed by the firepower of tanks and artillery on a scale never seen on the islands of the South Pacific. The division’s veteran infantrymen knew that few of them would make it through the invasion alive and unwounded.

The 40th Infantry Division began preparing for its role in the invasion at its base on the island of Panay. Its units took in replacements for the soldiers lost in the Philippine campaign, reequipped, and trained for the intense combat expected on the home islands of Japan. An amphibious training school set up by the Army at Subic Bay, the recaptured U.S. Navy base on Luzon, sent entire infantry regiments at a time to practice landings on beaches on Panay and Negros.

On August 16, the 160th Infantry Regiment was at sea on its way to a practice amphibious assault when an unexpected announcement blared from the loudspeakers of the transport ships. The captain of each ship declared that B-29 Superfortress bombers had dropped bombs on Japan that each had the power of thousands of tons of explosives, and that to stop the destruction of the Japanese people by these new weapons, the emperor of Japan had announced that his nation would surrender and end the war.

There was silence on board Lt. James Kim’s ship after the announcement. No one could believe that some unknown wonder weapon had suddenly caused the Empire of Japan to give up. Then for several minutes, the soldiers and sailors talked among themselves, all of them certain that there had been some sort of mistake and that the news could not be true.

Everything changed when the captain’s voice boomed out of the loudspeakers again. He repeated his announcement, and this time—after the men’s lack of reaction during the past several minutes—emphasized that it was no joke.

Suddenly every man on board was shouting in celebration. Fireworks then flew from ships in the convoy into the night sky as antiaircraft gun crews elevated their rapid-fire guns and fired bursts of tracer rounds into the air. The sailors manning the guns threw all discipline and caution to the winds and fired away, expressing the sheer joy that everyone on board felt.

The war was over, and the deadly mission that they had been training for at that very moment would not happen. They were not going to have to invade Japan. They were going to survive the war, and soon they would be going home.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.