Elements of the 40th Infantry Division on Panay again boarded amphibious assault ships during the night of March 28, 1945, this time for a landing on the west coast of the neighboring island of Negros. The 185th Infantry Regiment landed on the west coast of Negros the following morning and advanced inland. The 160th Infantry Regiment, minus its 2nd Battalion, landed the next day. They encountered little opposition as they advanced, for the Japanese had again abandoned the coast of the island and withdrawn into its interior, to make their stand on hills fortified like those in the Bamban Hills on Luzon.

The 160th Infantry Regiment found the enemy’s main line of resistance a few days later, at a hill dominating the valley through which it was advancing. Designated Hill 3155 after its elevation, it was soon renamed Dolan Hill in tribute to 1st Lt. John Dolan, the first officer killed trying to capture it.

Dolan Hill was the anchor of another formidable Japanese fortified area. From its peak, the Japanese could observe and fire down on approaching U.S. troops with their mortars and 20mm automatic cannons. Its slopes and those of the smaller hills around it were studded with bunkers, positioned and built with the skill that the Japanese had shown throughout the campaign. Machine guns inside the bunkers were ready to rain bullets on advancing Americans.

The defenders were a ragtag force scraped together from the remaining Japanese forces in the area: remnants of two infantry battalions, and soldiers from transport, airfield, and harbor units with no trucks, airfields, or harbors left to operate. They were not the elite Japanese airborne troops and marines that the 40th Infantry Division had fought in the Bamban Hills, but they were equally ready to fight to the death in their fortifications.

The 160th Infantry would spend almost two months in a seemingly endless struggle to take Dolan Hill. Its advance to the hill took two whole weeks. Japanese troops fought delaying actions by day, and when the Americans went into defensive perimeters at night, the Japanese infiltrated the forests around them and raided under cover of darkness. As the 160th closed in on Dolan Hill, the mortars and 20mm guns opened fire, stalling the advance and killing and wounding men. The 160th Infantry had to fight through rugged terrain cut by ravines and take a ring of fortified hills before its men finally reached the bottom of Dolan Hill.

For two days, artillery bombarded Dolan Hill in an attempt to weaken its defenders, and on April 17, the regiment’s 1st Battalion began the assault. They advanced slowly, needing to cling to tree branches and roots to climb up the hill’s steep slopes and eliminate enemy positions. They moved forward steadily for the entire first day, dug in for the night, and resumed their advance on the second day until they were within a hundred yards of the summit. When night fell, they established another defensive perimeter and prepared for the final assault the next morning.

Night attacks sent them retreating down the hill. From their bunkers in the heights above, the Japanese hurled grenades and explosive charges and unleashed barrages of mortar bombs. Unable to fire back at the unseen enemy and too close for their artillery to intervene without risking hitting them if they stayed, they had to fall back. The artillery bombarded the summit to cover their withdrawal and kept hammering it for the remainder of the night.

Day after day, the 160th Infantry resumed its attempts to advance to the top of Dolan Hill, and Japanese resistance stopped them with almost nothing to show for their efforts and sacrifices. They were in a struggle reminiscent of the fighting on the western front in the First World War, pinned down by Japanese machine guns in a network of bunkers connected by trenches and having any attempt to move forward or even raise a head to look around met by a hail of bullets.

Even the mundane task of keeping the assault force supplied was a struggle on the steep, trackless hill. The 160th Infantry resorted to hiring hundreds of Filipino civilians to carry food, water, and ammunition to the front line, freeing its own men to fight in the dwindling ranks of the infantry companies on the hill. Engineers began to bulldoze a switchback road up the hill to ease the burden of moving up supplies as the battle went on and on.

While the battle for Dolan Hill raged back and forth, Lt. James Kim did all that he could to gather intelligence on its defenses and support the fight. After James’s 1st Battalion first advanced up the hill, he regularly visited the infantry companies on the front line and sent the men of his intelligence section to stay with the company commanders full time and send back daily reports. He demanded that the division’s Japanese-American interpreters, who were normally kept at the divisional and regimental headquarters, be sent to the battalion and its front-line infantry companies to help encourage Japanese soldiers to surrender.

The costly stalemate dragged on for so long that the commander of XIV Corps came to confer with the commanders of the 40th Infantry Division and the 160th Infantry Regiment. Observing the council of war were the officers of the 160th Infantry, including Lt. James Kim and Capt. Walter O’Brien, the regimental chaplain. They watched Col. Raymund Stanton, the regimental commander, and Maj. Gen. Rapp Brush, the division commander, brief XIV Corps commander Lt. Gen. Oscar Griswold on the situation on Dolan Hill and tell him that the regiment could take the hill if given a few airstrikes to help soften up the enemy.

General Griswold then unexpectedly turned to Father O’Brien and asked for his thoughts on what his regimental and division commanders had just said. “Padre, you’ve heard all of this. What’s your opinion?”

The chaplain, a Catholic priest of the Capuchin order, had been ministering to the dead and wounded from Dolan Hill. He could not accept his commanders’ ongoing optimism about the battle, and now he had an opportunity to speak for himself and the other officers of the regiment whose men had fought and died to take the hill, without success. He struggled to find the right words for his thoughts in what appeared to be the only opportunity for anyone to speak freely. He then gave the general the simplest answer that he could: “That’s a lot of crap!”

General Griswold smiled at the padre’s plainspoken honesty. General Brush and Colonel Stanton did not. Father O’Brien expected to be reprimanded, but no reprimand came. Instead, his opinion ended up prevailing when General Griswold issued his orders for the next attack on Dolan Hill.

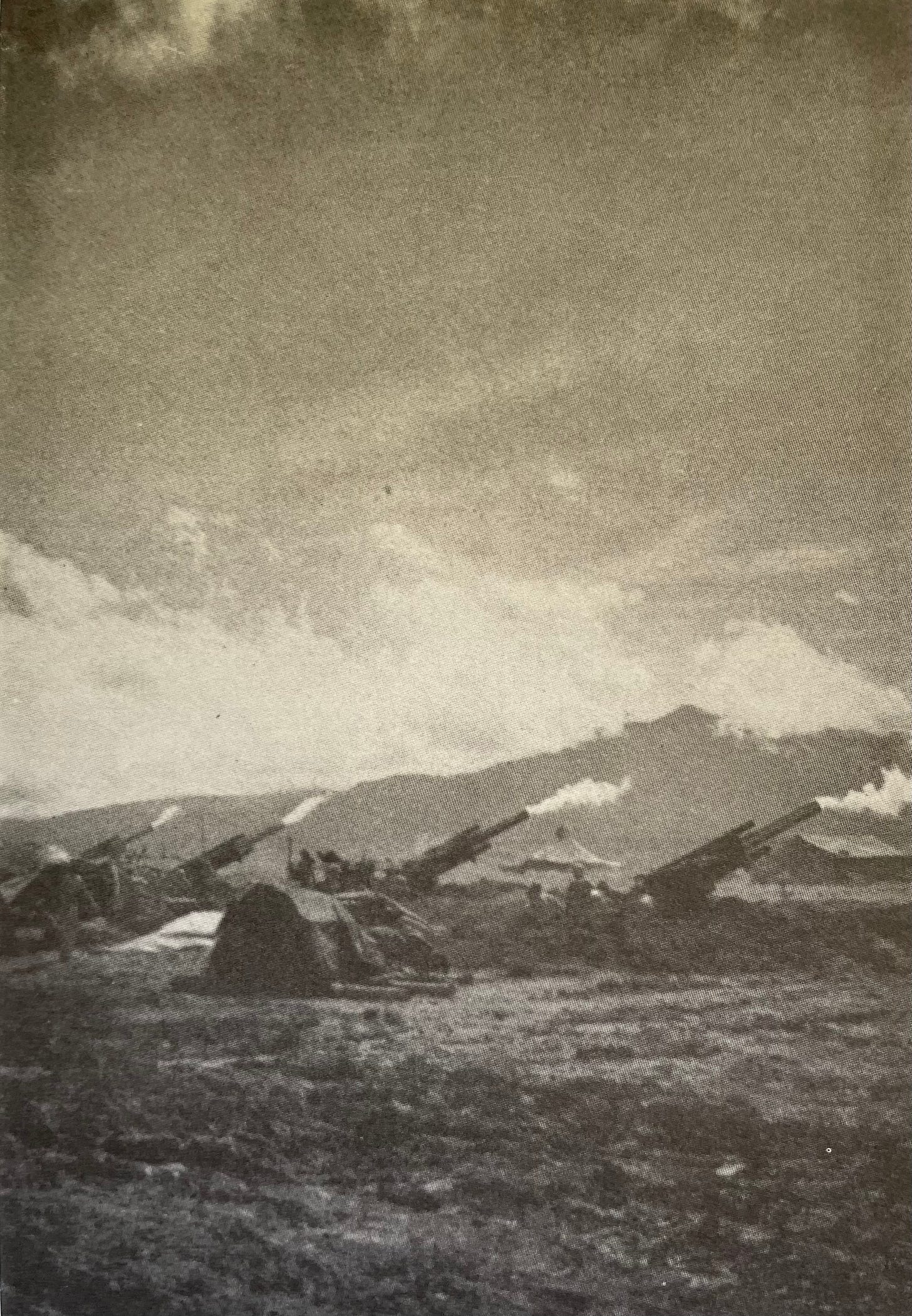

The attack began with all of the infantry withdrawing from the hill, giving up the ground they had fought and bled to gain to put a safe distance between themselves and the massive storm of steel and explosives to come. Then the 40th Infantry Division’s artillery opened up, commencing a barrage of 105mm and 155mm howitzer shells that began on May 11 and continued all day. It continued through the next day, then another, and for a fourth day, firing day and night. The artillery concentrated all of its fire on one part of the hill, then moved to others, systematically destroying its entire surface. P-38 Lightning and F4U Corsair fighter-bombers and A-20 Havoc twin-engine bombers strafed and bombed the hilltop, flying over a hundred sorties that further destroyed the hill’s defenses.

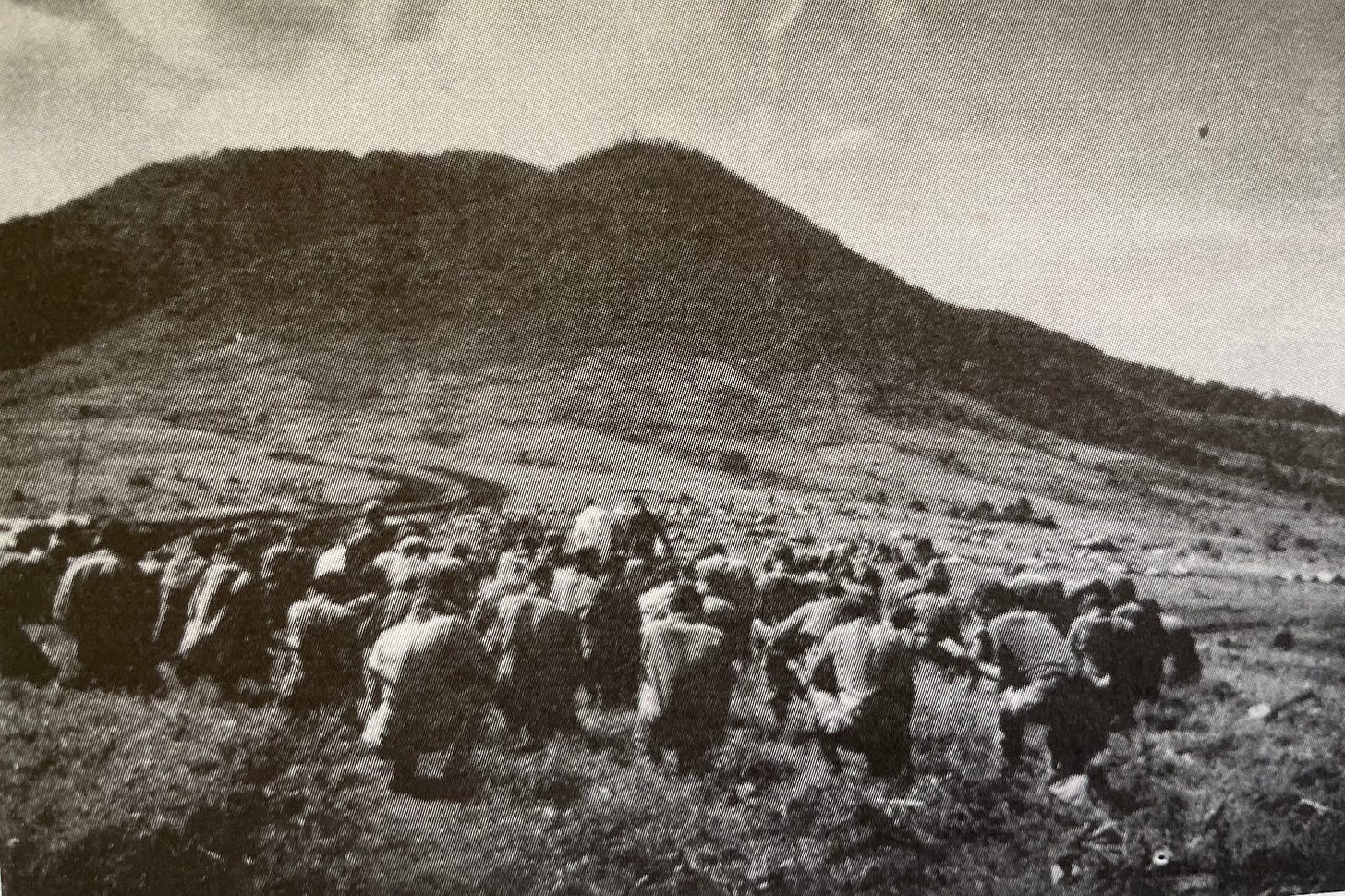

In the morning of May 15, the infantry finally moved forward up Dolan Hill. They found hill and its Japanese defenders devastated by the four days of artillery bombardment and air strikes. The trees that once densely covered the slopes had disappeared, reduced to stumps. Pillbox after pillbox was found blasted apart. More than two hundred dead bodies of the enemy were scattered around. The 160th Infantry reached the top of Dolan Hill completely unopposed, not seeing a single Japanese soldier until they found a few dazed survivors below the summit.

After the capture of Dolan Hill, the 40th Infantry Division continued its operations to clear Japanese forces from Negros for the rest of May 1945 and into the month of June. By early June they had eliminated most of the Japanese forces on the island, and the last remnants were falling apart, running out of supplies and barely able to eat enough to stay alive. Demoralized Japanese soldiers began to surrender after the 40th Infantry Division’s intelligence section set up loudspeakers to broadcast appeals to surrender, delivered by the section’s Japanese American interpreters and a Japanese prisoner of war.

Their task of liberating the island of Negros accomplished, the 40th Infantry Division turned over further operations on the island to other U.S. forces and Philippine guerrillas. All 40th Infantry Division units on the island returned to Panay to prepare for their next mission: the invasion of Japan.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.