Peter and Richard Kim’s refugee train from Kukong arrived in Hengyang with the city under attack by Japanese air raids and overwhelmed by mass panic. Japan’s Operation Ichigo offensive was overwhelming the defenders of Changsha, less than 100 miles to the north, and the population of Hengyang was evacuating the city. In the mobbed train station, Peter and Richard’s group struggled to find room on another train crammed with refugees, fleeing south away from the Japanese onslaught.

The train reached Kweilin in the morning of June 8, and Peter and Richard’s group found the train station master expecting them. The station master happened to be a childhood friend of their leader Peter Chang, and Chang had been able to inform him of the group’s escape from Shanghai and to expect them to arrive on a train from the north. Finally, after a month on the run, they had found refuge in free China.

The station master had a telegram for Peter Kim. It was from Walter Fowler, responding to Peter’s telegram from Kukong. Somehow, Fowler’s message had been forwarded to the Kweilin train station, and the station master had been waiting for someone named Peter Kim to arrive. Fowler stated that he had radioed his son in law Robert Biesel to notify Anker Henningsen of Peter’s arrival, as Peter had requested, and that Peter should contact him upon reaching Chongqing. Incredibly, Peter’s longshot attempt to use a cryptic telegram to secure the assistance of a total stranger in distant Chongqing, on the advice of his friends at the Swiss Consulate in Shanghai, had worked out.

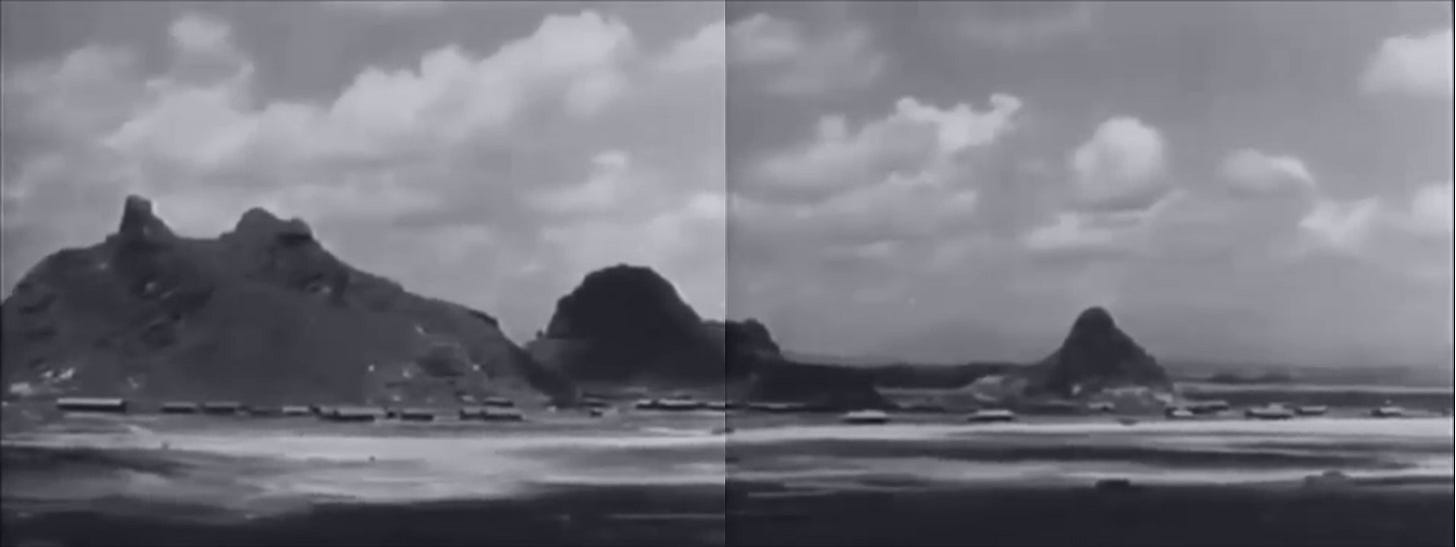

An important appointment was also waiting for Peter in Kweilin. He was summoned to meet a U.S. Army intelligence officer at the city’s airfield, which was the main base for the U.S. Army Air Forces in central China. Peter was taken to the airbase, a sprawling complex of more than 500 buildings below a row of the region’s limestone hills, where he found that another incredible coincidence had occurred.

The American intelligence officer was Captain Maxwell Becker, the Kweilin-based operator for a top secret U.S. intelligence organization in China called the Air Ground Aid Section (AGAS). AGAS had been created in late 1943 to conduct rescue operations for downed American airmen in China. Escape routes through Japanese-controlled territory and networks of people who could covertly help move lost Americans along them were crucial to AGAS, so Becker was constantly on the lookout for any source of information on them. Peter’s recent experience escaping from Shanghai to Kweilin was exactly what Becker was looking for.

There was yet another coincidence for them to talk about. Becker had been born and raised in Korea, and he and Peter had lived improbably parallel lives there.

Becker had been born in Pyongyang, the son of an American science professor teaching at Union Christian College, and he and Peter had moved from Pyongyang to Seoul at almost the same time in 1915. Becker’s father moved to Seoul to become part of the original faculty of Chosun Christian College when it was founded that year, and Peter’s father had moved there to study at Chosun Christian College’s medical school. Three decades later, the fortunes of war had brought them together in Kweilin.

Peter soon discovered another person from his family’s past was now a U.S. Army officer in China. With the help of the U.S. Consulate in Kweilin, he succeeded in finding his childhood best friend, Roy McNair, Jr. More than a decade earlier, after the April 1932 bombing of the Japanese military command in Shanghai, the McNair family had protected him and his family from a Japanese manhunt. Now Captain Roy McNair was the Assistant Military Attaché in China, stationed in the Nationalist capital of Chongqing.

The senior U.S. Military Attaché in China was Colonel Morris DePass, one of the U.S. Army’s most experienced China hands, whose expertise also extended to Korea. Years earlier, in the first weeks after Pearl Harbor, Colonel William Donovan—soon to become the founder and director of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)—had asked DePass to devise a plan to recruit Koreans, who had been resisting Japanese imperialism for decades, for U.S intelligence operations against Japan in China. Now Roy McNair had found him one with proven loyalty to the United States who was eager to join the fight against Japan. Peter’s value was obvious to DePass, who moved to recruit him right away.

DePass arranged for Peter to fly to Chongqing on a U.S. military transport plane. Peter accepted, but with a heavy heart, because Richard had no place in these plans. Peter would have to leave his teenaged brother behind in Kweilin, with the Imperial Japanese Army advancing toward the city. All that he could do was ask his contact at the U.S. consulate to help look after Richard for him.

On July 8, Peter boarded a C-47 transport plane for the flight to Chongqing that would change the course of his life.

Richard remained in Kweilin, working as a laborer at the airbase, until the unstoppable advance of Operation Ichigo drew near. Changsha had fallen on June 19, then Hengyang on August 8. With Kweilin the next objective for the Japanese, the U.S. forces hastily evacuated and demolished the airbase, cratering the runway, burning the buildings, and destroying gasoline, ammunition, and other supplies so that the Japanese could not capture and use them. Convoys of U.S. Army trucks rolled away with personnel who could not be evacuated by air.

Richard left Kweilin during this ignominious retreat. Peter’s friend at the consulate arranged for Richard to join a retreating U.S. military unit, instead of having to fend for himself, alone among masses of Chinese civilians fleeing by train or on foot. Richard got to ride in the back of a U.S. Army truck, sitting in its cargo bed between barrels of diesel fuel. The truck was part of a convoy that reached the next U.S. airbase at Liuzhou, 100 miles to the south, by the end of the day. The next day it headed west, toward the safety of the U.S. airbase at Kunming in the foothills of the Himalayas, more than 400 miles away.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.