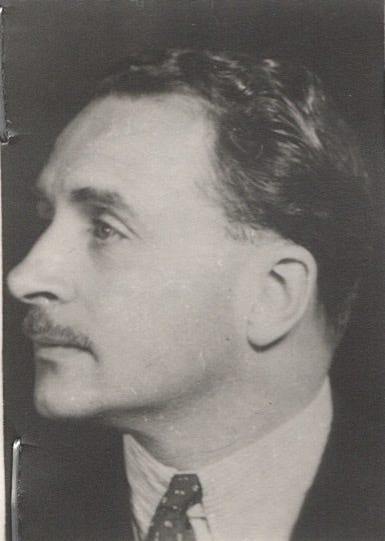

Emile Fontanel, Heroic Diplomat of WWII

The Swiss Consul Who Protected Americans in Japanese-Occupied Shanghai

Emile Fontanel, Swiss Consul General in Shanghai from 1938 to 1946, took on the difficult task of protecting the rights of Americans living under Japanese occupation and internment in Shanghai from December 1941 to the surrender of Japan in 1945. For almost four years, Fontanel was responsible for monitoring Japanese treatment of U.S. citizens and administering life-saving assistance programs for them. At war’s end he secured the release of the civilians from Britain, the U.S., and the other Allied nations whom the Japanese had held captive for years. During these difficult times, Fontanel befriended Peter Kim and helped him and his family to survive the war.

Fontanel was an experienced diplomat with two decades of experience in Swiss embassies and missions in Washington, London, Berlin, Warsaw, Budapest, and Madrid when he became Consul General in Shanghai in April 1938. Serving in Madrid during the first year of the Spanish Civil War introduced him to the difficulties of acting as a diplomat in wartime, but nothing could have prepared him for Shanghai during the Second World War era.

Japan had attacked and occupied the Chinese-governed parts of the city six months earlier, and on December 8, 1941, Japanese forces marched into the International Settlement to complete their conquest of Shanghai. When Switzerland became the intermediary between the United States and Japan in matters involving civilians of the two combatant nations, Fontanel was thrust into the role of acting on behalf of the U.S. government to assist American citizens in Shanghai.

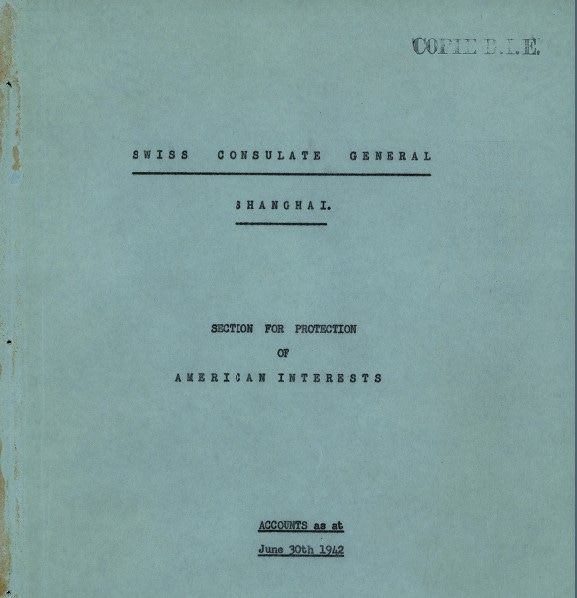

Fontanel created a Section for Protection of American Interests that soon began administering a key U.S. program to assist Americans in Shanghai. In April 1942, the consulate began distributing loans to U.S. citizens under a U.S.-government funded program created by the U.S. Department of State and the Swiss Foreign Ministry. These funds enabled Americans to buy food and other necessities in Shanghai’s markets, in the absence of jobs and incomes that had been lost when foreign-owned businesses had been confiscated by the Japanese. Betty Kim, the only U.S. citizen in the Kim family in Shanghai, began receiving these loans in October 1942.

The Section for Protection of American Interests administered the repatriation of U.S. citizens from Shanghai on the Swedish exchange ship MS Gripsholm. In the summer of 1942, the section worked with Peter Kim of the American Association of Shanghai to select and organize Americans for repatriation. Their joint efforts resulted in 639 U.S. citizens leaving Shanghai in July 1942 for the voyage home on the Gripsholm. They also left a positive impression of Peter Kim on Fontanel, who became the first of many senior officials to see the previously obscure English-speaking Korean who considered himself to be an American as an invaluable asset in the world war.

When Japanese authorities herded Americans, British, and other citizens of the Allied nations into internment camps in January-April 1943, Fontanel hired Peter Kim in March 1943 as the Swiss Consulate’s point person for looking after interned Americans. Peter organized the delivery of relief supplies from the Swiss Red Cross, reported problems in the camps, and organized the release of almost 1,000 internees for a second repatriation voyage by the Gripsholm in September 1943.

Fontanel and his staff helped Peter Kim when the time came for their now-colleague and friend to escape Shanghai. They gave him money that they had collected to pay for the costs of smuggling him and his brother Richard to free China, and Fontanel promised to look after his family and ensure that they would continue to be supported while Peter was away and completely cut off from contact with them. One of Fontanel’s subordinates advised Peter to look for a specific U.S. official in Chongqing who might be willing to help him, since Peter had fought to add his son-in-law to the repatriation list for the second Gripsholm exchange voyage.

Seven years after Emile Fontanel took over as Swiss Consul General in Shanghai, the war finally came to an end, and he acted decisively to protect the 7,000 Allied nation civilians who remained in Japanese internment camps. Hours before Emperor Hirohito’s surrender announcement at noon on August 15, 1945, Fontanel summoned all Japanese camp commandants to a meeting at his official residence (shown above) to tell them that the war was over and they were to relinquish control of the camps immediately. He then offered his residence as the safe house, protected by international law, for the U.S. intelligence mission that flew into Shanghai on August 19 — with Peter Kim as one of its leaders — to take over the internment camps and rush U.S. aid to them. That story will be told at some time in the future.

After the war, Emile Fontanel continued his career in the Swiss diplomatic service, with further overseas assignments in Barcelona and Montevideo, before retiring in the mid-1950s. He passed away in 1979.

Biographical details on Emile Fontanel are from the website Dodis — Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland, at this link.

Information on the Shanghai internment camps and Emile Fontanel’s actions at the end of the war is from Greg Leck’s book Captives of Empire: The Japanese Internment of Allied Civilians in China, 1941-1945. Captives of Empire can be purchased here.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.