The Kim family had finally been completely reunited in Shanghai in October 1945, but most of them were stuck there as the city became part of Nationalist China and the last remnants of its foreign communities departed. In a cruel irony, Peter Kim was a U.S. Army lieutenant assigned to assist the U.S. Consul in repatriating Americans stateside, but he was ineligible to go with them, not being a U.S. citizen.

Colonel Marshall Carter and Brigadier General George Olmsted, Peter Kim’s commanding officers, stepped forward to right the wrong that the nation’s immigration laws had created. Carter came up with a daring, long-shot plan: to lobby Congress to enact a private law—an act providing benefits to a specific individual—granting U.S. citizenship to Peter Kim.

Olmsted elevated the issue all the way up the chain of command to the Supreme Allied Commander in China, Albert Wedemeyer. General Wedemeyer endorsed the plan and gave it the weight of his name, signing a letter that unequivocally recommended granting U.S. citizenship to Peter Kim for his outstanding actions with the U.S. forces in China.

Fortuitously, the right envoy to convey the message to Congress was at that moment in Shanghai preparing to fly to the United States. He was Captain Robert Peaslee, Peter Kim’s friend and comrade in arms in Kunming, Chongqing, and Shanghai. Peaslee, scheduled to return to the U.S. for demobilization in late October, was from a Minnesota family that was prominent in the state’s Republican Party and connected to Senator Joseph Ball, a Republican from Minnesota, who happened to have become especially interested in causes similar to that of the Kim family.

Joseph Ball had a history of acting against his own party when necessary to address crucial wartime problems. As a newly elected senator in 1940, he had broken with the party’s isolationists to support the foreign policies of President Franklin Roosevelt. He had crossed party lines to endorse Roosevelt’s reelection in 1944. After the war, he became concerned with addressing the problems of the millions of displaced persons in war-torn Europe who had lost everything and had nowhere to go.

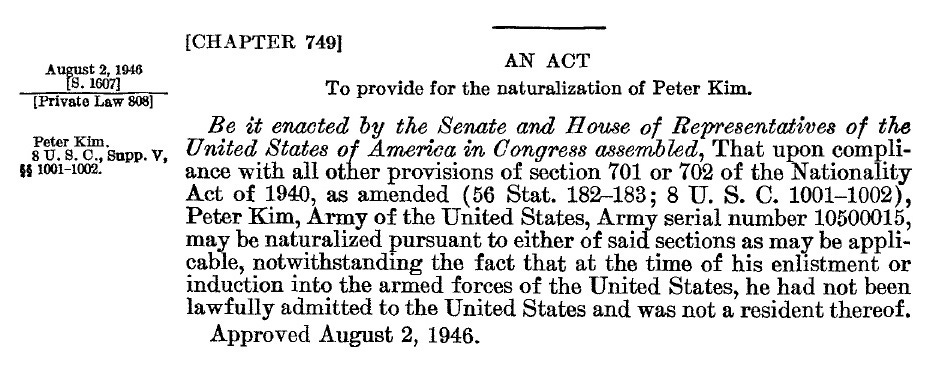

Peaslee flew across the Pacific and then on to Washington for a meeting with Ball. Peter Kim’s story, backed by the endorsements of the U.S. commanding general and other high-ranking officers in China, made a powerful impression on the senator, who immediately agreed to submit a bill for the naturalization of Peter Kim to the Senate Committee on Immigration. True to his word, on November 19, 1945, Ball introduced Senate Bill 1607, “A Bill to Provide for the Naturalization of Peter Kim.”

Getting the bill through the committee and to the floor of the Senate for a vote was a months-long process, and during that time, Peter Kim’s commanders had to deal with another crisis over his legal status. In January 1946, after a long dispute over the propriety of his commissioning in August 1945, Army bureaucracy forced him to revert to the enlisted ranks. General Wedemeyer’s staff responded by sending a demand to the Pentagon that the War Department make him an officer, waiving the U.S. citizenship requirement—a rare action during the Second World War or any other era. The War Department granted the waiver, and on February 25, 1946, Peter Kim was sworn in and properly commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army.

In June 1946, Senator Ball’s bill finally made it out of the Senate Committee on Immigration to face a vote on the floor of the Senate, and Ball found a member of the House of Representatives willing to introduce the legislation in the House—Walter Judd, a Republican also from Minnesota’s congressional delegation. Judd, a staunch anti-Communist who had served as a medical missionary in China in the 1930s before going into politics, introduced the House bill for Peter’s naturalization as a U.S. citizen in mid-July.

The Senate voted on the bill on July 17, and it passed as Private Law 808, “An Act to Provide for the Naturalization of Peter Kim.” President Truman signed the act into law on August 2, 1946.

The eldest son of Kim Chang Sei, who had dreamed of himself and his family becoming Americans and had ended his life when that dream was shattered, was at last welcome to become an American by citizenship as well as in spirit. Two decades had passed, and years of wartime sacrifices with no expectation of anything in return had been necessary to make it possible.

Peter Kim finally became a U.S. citizen when he swore the oath of allegiance to the United States on December 4, 1946. It happened in Shanghai, where his family’s American journey had been diverted for two decades.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, which will be available on June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, on Amazon at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.