The announcement of the surrender of Japan suddenly changed the mission of the U.S. forces in China from fighting the war to securing the peace. Their top priority became protecting the lives of people from the Allied nations, both military prisoners of war and interned civilians, languishing in Japanese prison camps.

To liberate them, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) headquarters in Chungking planned a wave of rescue missions, each given a bird code name: Operation Magpie to Beijing, Operation Flamingo to Harbin, Operation Cardinal to Shenyang (Mukden), Operation Duck to Weixian (Weihsien), Operation Eagle to Seoul, Operation Pigeon to Hainan Island, Operation Canary to Formosa, Operation Quail to Hanoi, and Operation Raven to Vientiane.

U.S. Forces–China Theater commander Lt. Gen. Albert Wedemeyer ordered that the OSS would be responsible for the missions to Beijing, Harbin, Shenyang, the Shandong Peninsula, and Seoul, while the Air Ground Aid Section (AGAS) would command the missions further south, including the one to Shanghai.

Peter Kim was indispensable to the mission to Shanghai. His first-hand knowledge of the city and its internment camps was unique in all of the U.S. military and intelligence organizations operating in China, as was his experience dealing with the Japanese occupation authorities in Shanghai. His commanders, Brig. Gen. George Olmsted and Colonel Marshall Carter, went all the way up the chain of command to secure him a place on Operation Sparrow.

Wedemeyer’s deputy chief of staff, Brig. Gen. Paul Caraway, approved his presence on Operation Sparrow and ordered that he go as an officer. Peter shed his enlisted rank of Technician Fifth Grade—equivalent to a corporal—and became 1st Lieutenant Kim, U.S. Army.

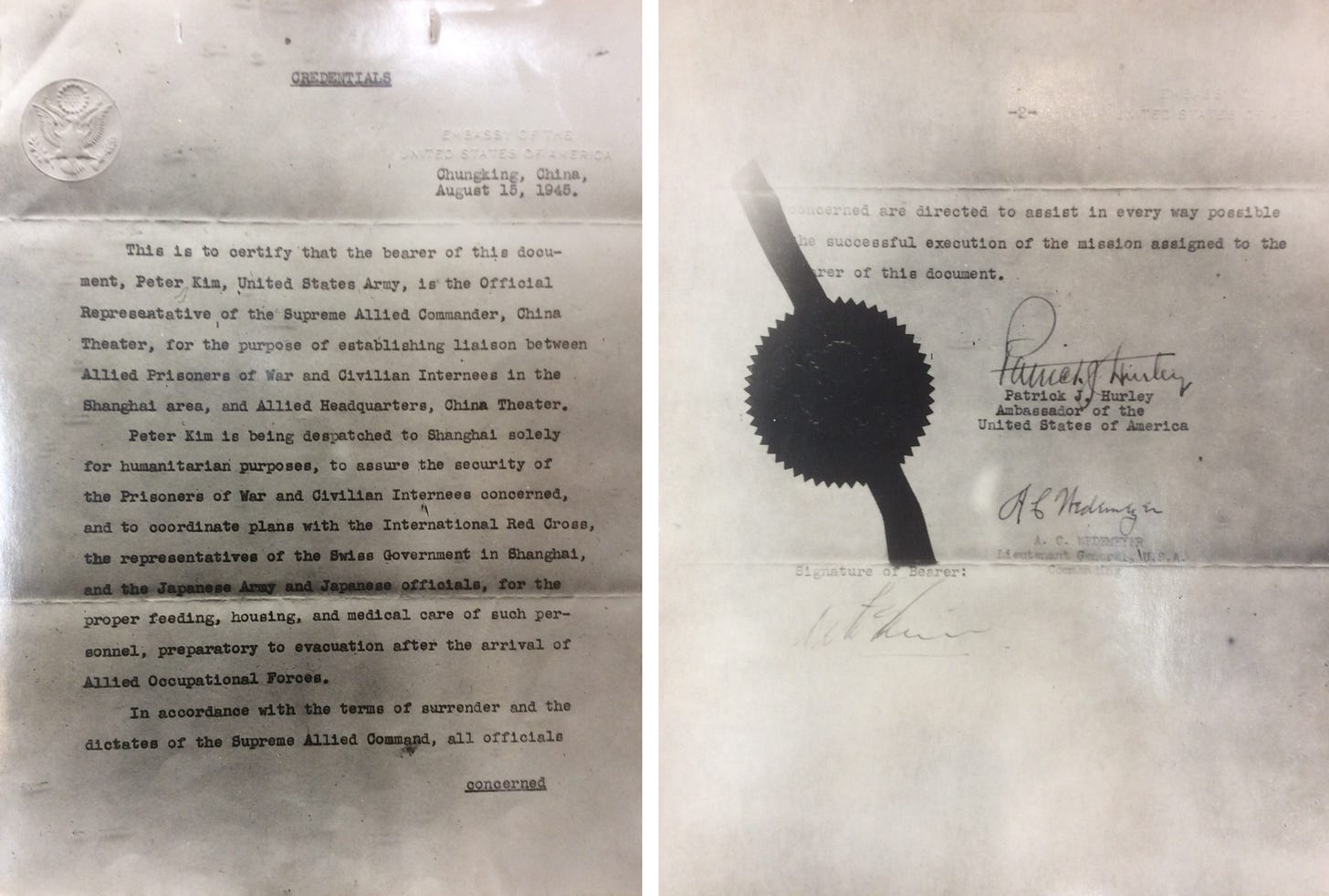

The sudden commissioning was necessary because Peter Kim was going on Operation Sparrow as the Official Representative of the Supreme Allied Commander, China Theater, General Wedemeyer. Operation Sparrow would deliver him to Shanghai to administer assistance to the interned civilians and prisoners of war, and only an officer would have sufficient stature with the other officers commanding the mission and with the Japanese authorities in Shanghai to perform this momentous task.

There was a critical problem, though. Peter Kim was not a U.S. citizen, and therefore not legally eligible to be made an officer in the U.S. Army. No one in the chain of command had remembered this crucial fact about him in the hasty planning of an array of extraordinarily complicated rescue missions from Manchuria to French Indochina, involving multiple military and intelligence organizations. At first he wanted to refuse to put on lieutenant’s bars, concerned that he was doing so on a questionably legal basis that could expose him and the entire chain of command above him to scrutiny if anything went wrong, but he had no choice but to follow orders in the rush to join and organize the mission.

Colonel Carter and Counselor Ellis Briggs from the U.S. Embassy in Chungking met Peter Kim to present him with his credentials just before he boarded a C-47 that flew him to join the Operation Sparrow team assembling in Kunming.

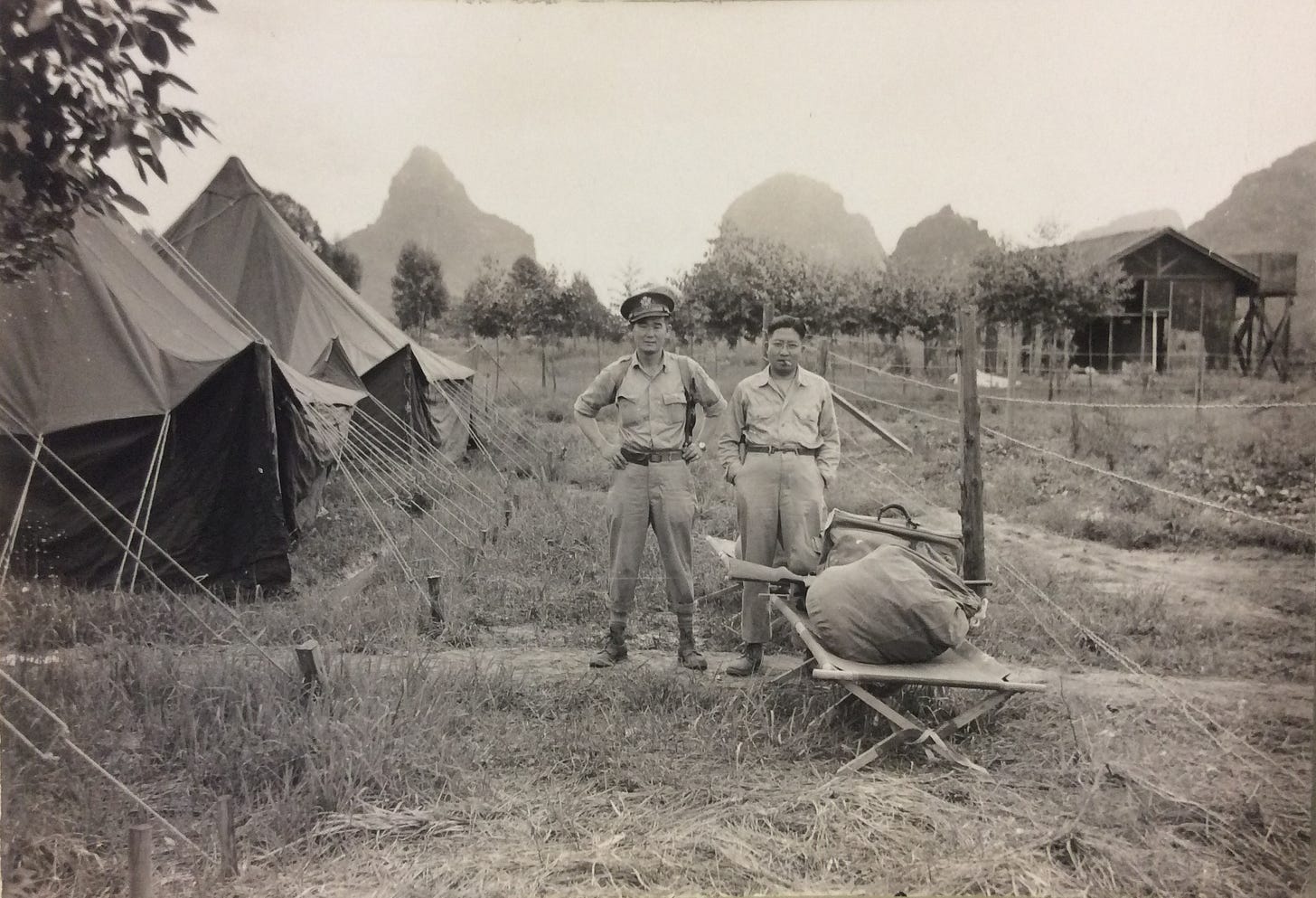

Peter Kim became part of a team of ten U.S. military personnel and two Chinese civilian advisors, commanded by Major Preston Schoyer of AGAS, that took off from Kunming in two C-46 Commando transports on August 17. With Shanghai 1,200 miles away, the mission staged through two U.S. forward airbases to refuel and rest before the final flight to Shanghai. During the night of August 18, while at the U.S. airbase at Liuzhou, they received a radio message reporting an important development in Shanghai.

Swiss Consul Emile Fontanel, Peter’s friend and former employer, had summoned the Japanese commandants of the internment camps to a meeting to tell them that the war was over, their authority over the camps would cease immediately, and they were to hand over the camps to a U.S. Army humanitarian mission that would arrive soon.

With the situation in Shanghai as prepared for their arrival as it could be, Operation Sparrow took off for the final leg of its journey in the morning of August 19. At the end of their 880 mile flight they would find out whether the still-undefeated Japanese forces in Shanghai would receive them without hostilities or would instead shoot down their defenseless transport planes.

This series previews my upcoming book Victory in Shanghai: A Korean American Family’s Journey to the CIA and the Army Special Forces, whose publication is expected by June 1, 2025. You can pre-order it now through Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, at this link, on Amazon at this link, or through your favorite local independent bookseller.

Subscription to this series is free.

If you know anyone who may be interested in this series, please share it with them.